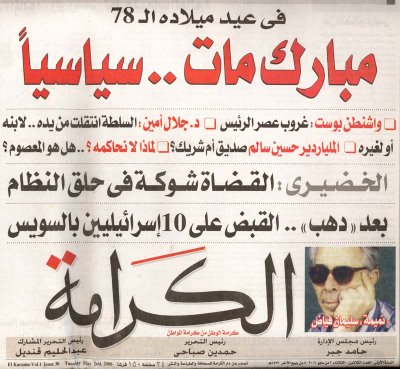

I’ve been watching with intense interest and much fascination three elections that have once again pitted members of the Muslim Brothers against members of the ruling regime. These are the internal elections for parliamentary speaker and deputy speakers, the trade union elections, and the student union elections. The press and assorted commentators have rightly noted similarities with the parliamentary polls, especially widespread thuggery and intimidation of opposition forces, broad administrative interference to block opposition gains, and the utter disregard for court rulings suspending faulty elections. But the common tendency to reduce these elections to the age-old contest between Ikhwan and regime captures only half the story, and the less intriguing half at that.

I’ve been watching with intense interest and much fascination three elections that have once again pitted members of the Muslim Brothers against members of the ruling regime. These are the internal elections for parliamentary speaker and deputy speakers, the trade union elections, and the student union elections. The press and assorted commentators have rightly noted similarities with the parliamentary polls, especially widespread thuggery and intimidation of opposition forces, broad administrative interference to block opposition gains, and the utter disregard for court rulings suspending faulty elections. But the common tendency to reduce these elections to the age-old contest between Ikhwan and regime captures only half the story, and the less intriguing half at that. (Photo courtesy of Alltalaba.com).

The other half is the struggle for undistorted, unabridged representation. The MPs who made a symbolic bid to unseat chronic parliamentary speaker Fathi Sorour, the resourceful workers who energetically exposed their institutions’ unfree elections, the brave students who organised parallel elections—all were activating the fundamental democratic principle of representation. I don’t mean some rarefied concept in political theory, but the demand to be consulted on decisions and practices that affect one’s life. I mean a mechanism to organise binding consultation, a procedure for the management of conflicting interests, and a process that holds the potential to modify existing interests. Barring direct democracy, the principle of democratic representation is the only legitimate bottom-up selection mechanism to manage the affairs of complex collectivities. It would thus be a grave misreading to reduce recent sub-national elections to nothing more than a contest between the Ikhwan and the regime. If we get past such sensationalism and unthinking parroting of the obvious, it is clear to me that the elections revolve around the struggle for adequate representation, a battle that is at the core of the drama of democracy.

Fiercely contested sub-national elections have been a consistent and lively feature of the post-1952 Egyptian political landscape. Internal elections to every sports club, faculty club, chamber of commerce, professional association, student union, actors’ union, and some public sector boards are heated affairs, much more ‘real’ than parliamentary elections and therefore of paramount importance to the regime. Far from being staged rituals orchestrated by the ruling regime as a serviceable safety valve, sub-national elections are real contests involving real issues that all Egyptian regimes have tried to control and obstruct. Recall the phalanxes of riot police and security forces during the Alexandria Chambers of Commerce elections this past May. And remember the security forces’ blockage of all Alexandria University campus entrances in April to prevent the faculty club from convening its long-suspended internal elections. Undeterred, 800 professors convened their general assembly in the open air on the corniche sidewalk and freely elected a governing board. Now this is what democracy looks like.

For more perspective on the significance of the recent elections, let’s reach back even further than last spring and recall some salient facts. Nasser manipulated the internal by-laws of professional associations to pack their voter rolls with his supporters, and went further by not-so-subtly endorsing handpicked candidates. When judges defied his regime and issued their March 1968 statement, Nasser gave the green light to mobilise massive regime resources to interfere in the Club’s March 1969 elections and oust the reformists, installing a much more government-friendly board. Sadat did the same: when social protest at his domestic and foreign policies peaked, he dissolved the board of the ever-contentious bar association and handed down a draconian new law that decapitated the national student union movement, the notorious ’79 charter.

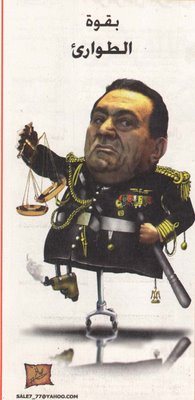

Mubarak is no different and has gone even further: he rammed through parliament an entirely new law crippling robust internal elections in the professional associations (Law 100/1993) and placing them under government receivership. A year later, he issued a law that replaced decades of bottom-up faculty election of university deans with top-down appointment by university presidents, all of whom of course are appointed by him (another law replaced election of village ‘umdas with appointment). After a protracted legal battle ably steered by the proud attorney Fatma Rabie’, lawyers successfully threw off the yoke of government receivership and resumed their suspended elections in 2001. Engineers and doctors are still battling to do the same. For those professional associations that escaped receivership (the Judges’ Club and the Press Syndicate), Mubarak was keen to see government-friendly incumbents hog all leadership positions. That old order was spectacularly overthrown when the general will of fed-up electorates ousted the rotten incumbents and voted in independent reformists in May 2002 and December 2005 (judges) and July 2003 and October 2005 (journalists).

Let’s remember that Nasser and Sadat were not battling Islamists in these institutions, but an assortment of leftists, liberals, nationalists, Islamists, and independents. That today the Islamists are at the forefront of the battle for associational autonomy should not obscure the fact that what is at stake is institutional autonomy and undistorted representation. If today the Ikhwan were replaced by leftists as the major electoral and political force, would the regime back off and let them carry on? Absolutely not. Just look at the regime’s multi-tiered involvement in the journalists’ and judges’ associations, two institutions where the Ikhwan historically have had and continue to wield very little clout. So while it’s comforting to dismiss the recent elections as yet more staging grounds for Ikhwan-regime competition, it would be entirely missing the point.

For the regime, elections in any sub-national institution pose an acute quandary. One the one hand, elections can perform useful functions. They can incubate tractable new elites, quash useless old ones, and provide a robust barometer of the moods of critical publics such as middle-class professionals, workers, and students. On the other, elections are extremely destabilising. They can incubate intransigent new elites, quash trusted old hands, and infect broader swathes of the population with dangerous new moods and demands. Above all, any elections are bound to activate demands for adequate, bottom-up representation. Whether it’s the determined voters of Damanhour and Doqqi, the enthusiastic electors in the professional unions, workers in the trade unions and businessmen in the cambers of commerce, the desire to elect representatives responsive to constituents is unwavering and arguably intensifying.

This is precisely why the ruling party dares not hold internal elections, and also why we see fierce NDP intraparty competition during the opportunity window opened up by parliamentary elections. If there were real elections within the NDP, would Gamal Mubarak and his cronies be where they are? Perhaps, perhaps not. And there’s the rub. The regime fears two things: the sheer uncertainty of the free play of interests, even if its own interests are triumphant. And the constant threat that its interests will be thwarted or challenged by rivals. Both fears fuel a multi-pronged strategy of engineering, manipulating, obstructing, rigging, and suspending sub-national elections. Such fears are also behind the decision to postpone municipal elections until 2008. More than simply fear of the Ikhwan, it’s these elections’ enormous uncertainties and real opportunities for popular mobilisation that drove the Mubarak regime’s deferral decision.

So if real democratic enclaves have always existed in this undemocratic regime, what’s new about the recent elections? Let’s review in ascending order of magnitude. The Ikhwan and independent parliamentarians’ symbolic bid to challenge Fathi Sorour’s endless tenure as parliamentary speaker was new, since everyone knows that all parliamentary leadership positions are jealously hogged by the very National, oh-so-Democratic Party. The attempt to reinvigorate the principle of internal parliamentary representation is significant; the closest that non-NDP MPs had come to such a manoeuvre was Ayman Nour’s running for deputy speaker after the 2000 vote (he received a surprising 169 votes). To be sure, no one expected the sticky Dr. Sorour to be dislodged from his favourite perch, and even if by some miracle he had been ejected, no one expected parliament to turn into a real creature forthwith. The democratisation of parliament and the parliamentarisation of Egyptian politics is a very long way off. But the Ikhwan’s move betokens renewed resolve to activate the principle of representation. Who’s to say that five or ten years down the line, we won’t see real, unpredictable elections for the post of parliamentary speaker? When it happens, we’ll likely look back at the maiden attempt in 2006 and ponder its long-term consequences.

Next, the trade union elections. I can’t remember the last time that these elections offered anything meaningful to write about, so why is this year different? Again, most accounts point to the Ikhwan’s new participation in what for the group so far has been mostly terra incognita. But there’s much more to it than that. Demands for real representation have long been brewing on Egyptian shop floors, fuelled by rapidly deteriorating work conditions and the dangerous erosion of the state-sponsored social safety net of yore. Over the past 15 years, the industrial labour force has been squeezed by soaring costs of living and unfair work conditions without a corresponding increase in official tolerance for worker collective action (much less collective bargaining). The rotten labour aristocracy that is the Egyptian Trade Union Federation (ETUF) has given up all pretence of worker representation and has instead embraced its role as first and foremost a state adjunct that polices workers and quashes any bottom-up attempts at independent representation.

Next, the trade union elections. I can’t remember the last time that these elections offered anything meaningful to write about, so why is this year different? Again, most accounts point to the Ikhwan’s new participation in what for the group so far has been mostly terra incognita. But there’s much more to it than that. Demands for real representation have long been brewing on Egyptian shop floors, fuelled by rapidly deteriorating work conditions and the dangerous erosion of the state-sponsored social safety net of yore. Over the past 15 years, the industrial labour force has been squeezed by soaring costs of living and unfair work conditions without a corresponding increase in official tolerance for worker collective action (much less collective bargaining). The rotten labour aristocracy that is the Egyptian Trade Union Federation (ETUF) has given up all pretence of worker representation and has instead embraced its role as first and foremost a state adjunct that polices workers and quashes any bottom-up attempts at independent representation.A wave of labour protests all over the country in 2006 against declining or stagnant wages, forced early retirement packages, and other pauperisation policies set the stage for last month’s elections. Workers began mobilising to push for real representation to protect their increasingly threatened interests. Sensing this, the government took pre-emptive measures starting back in August, administratively disqualifying independent candidates and establishing a tight-knit infrastructure of procedural obstacles. Workers immediately appealed to the administrative courts and secured countless rulings verifying myriad election violations, but the regime of course ignored the rulings and elections went ahead anyway. Many pro-regime labour aristocrats were thus ‘elected’ or retained their posts uncontested. Credible, independent worker rights groups such as the Helwan-based Centre for Trade Union and Workers’ Services (CTUWS) have copiously documented election irregularities and violations.

Up to this point, the story would be a sad but familiar echo of nearly every election in Egypt. But events then took a dramatic and highly unexpected turn. Early this month, 20,000 Mahalla textile workers staged a sustained and massive work stoppage against management’s decision to renege on election-related promises to pay two months’ worth of bonuses. Workers went head to head not just with management but with Ministry of Manpower Aisha Abdel Hadi and high-ranking State Security officers. They adamantly refused several compromises brokered by Abdel Hadi and resisted State Security’s transparent divide-and-rule strategies. Above all, Mahalla’s workers (including 7,000 women) managed to valiantly weather credible threats of violence and reprisal, arming themselves with tree branches and sleeping in shifts to be able to respond to any sudden crackdown. Consciously and deliberately, Mahalla’s workers jettisoned the politics of remonstrance and demanded full and unabridged citizenship rights. Remarkably, they won. The regime relented and management agreed to pay the full bonuses. Significantly, the strike ended with a worker petition drive that has so far collected 20,000 signatures for a vote of no-confidence in the recently “elected” company union. The struggle for real representation continues.

Cairo University students protest the 1979 Charter and State Security interference, April 2005 (AP Photo)

Cairo University students protest the 1979 Charter and State Security interference, April 2005 (AP Photo)Amr Hamed is an articulate, serious, doe-eyed student in his penultimate year of medical school at Cairo University. On a blindingly sunny day, he sits on a low campus wall shaded by outstretched, leafy tree branches, fighting off an annoying cold while being greeted by friends and well-wishers. Unlike other students buried in reading for their exams, medical school students have some leeway before their brutal examinations start in the spring. So the Qasr al-Aini campus is abuzz with voluble conversation and warm sociability; students munch on biscuits and sip soda pop, chatting for hours. Medical residents walk in twos and threes in their pristine white coats and stethoscopes; haggard nurses gossip about pesky patients; professors park their spiffy cars and disappear into the Dean’s building. And Amr Hamed ponders the recent turn of events that crowned him secretary-general of Egypt’s first nationwide student federation since 1979.

The story has a long history; let’s start in the heyday of student power after the protest wave of 1968-1972. Students were arguably one of the most influential societal sectors in the mid-1970s. In February 1976, at a national student union conference in Shibin al-Kom, students demanded a new charter and gave the president a one-month ultimatum until March 22, after which they vowed to stage a nationwide general strike. On March 21, as Sadat was travelling abroad, his vice-president Mubarak signed into law a charter that contained very robust measures of financial and decisional autonomy for student unions. Cairo University students’ weekly magazine al-Tullab became a key opposition outlet, well before the ‘platforms’ and then opposition parties issued their own newspapers. But after skyrocketing domestic opposition to Sadat’s foreign and domestic policies, Sadat revoked the ’76 charter and issued a new one in 1979, which decapitated the student movement by abolishing the national student union federation. Student unions were now confined to their individual campuses, with no nationwide coordinating structure. The '79 Charter also reinstated the requirement of a faculty guardian who supervised each union and had the power to veto its decisions and withhold its funding.

Mubarak’s control of Egyptian campuses reached deeper. Not content with sundering the links between campuses, for the past ten years security forces have routinely intervened in individual campus elections. They exclude all independent, leftist, and Islamist candidates to clear the way for the pathetic candidates of the pro-regime campus union, “Horus” (even their name smacks of illegitimacy). This is in addition to the various other indignities suffered by college students, from inadequate course materials to abysmal dormitory conditions to a general and rapid decline in the quality of all campus services. This long train of abuses finally led Egyptian students to organise parallel elections in November 2005, when 15 universities held elections for a Free Student Union (FSU).

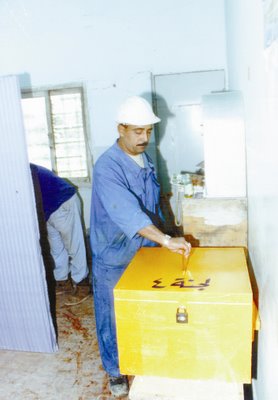

The initiative was repeated this year. Students organised a completely independent, parallel process from A to Z. They stipulated a four-day candidacy registration process, a three-day campaigning period, and a full day of balloting. They put together homemade transparent ballot boxes from plastic wrap and masking tape (I love it). They invited faculty members and human rights groups as poll watchers and ballot counters. And they invited uninterested, apolitical students to join in the ballot count.

In response, State Security hired thugs to intimidate students and faculty who participated in the FSU elections in Ain Shams, and the administration of al-Azhar University suspended students who ran and won in the FSU elections and referred them to disciplinary tribunals. Undeterred, students took matters a notch higher with the organisation of the first elections for a nationwide student union federation since 1976. Students from 12 universities participated (two elected student union leaders from each university for a total of 24 electors). The Muslim Brothers at the bar association hosted the election after the administration of Cairo University naturally refused. The Brothers of course have a vested interest since their fellow members are the overwhelming majority of elected student representatives on each campus, but as both Brothers and others emphasise, the FSU is a collective effort that includes Coptic, liberal, leftist, and Nasserist students, and several students with no set ideological commitments.

Amr Hamed from Cairo University’s faculty of medicine was elected as national secretary-general while Amr Abdel Bari from Mansoura University’s faculty of pharmacology was elected as assistant secretary-general. Asked why he thinks he got elected, Hamed is disarmingly modest, explaining that the symbolism of his university and the historic weight of his faculty within the university determined his fortunes. But watching him interact with his peers on campus tells a different story. Amr Hamed is first among equals. He does not carry himself with the arrogance of a leader or the strutting of a big man. He blends in with his constituents. He’s soft-spoken and focused, warm and congenial, and very very busy, gracefully fielding endless calls, discussions, and queries. The noon call to prayer sounds and his peers come to collect him to pray. I watch them walking off briskly and think, this is what democracy looks like. “The principle of appointment rules all across the country now,” he says, “that’s why this is significant.”

A spectre is haunting Egypt, the spectre of real representation. From 2000 to the present, parallel to the return of routinised street protest, there have been significant stirrings for genuine representation among the country’s vital sectors. Lawyers took back the bar in 2001 and 2005, judges elected a bold new leadership team in 2002 and 2005, journalists did the same in 2003 and 2005, Kifaya did serious representation work in 2004 and 2005, actors elected a more representative chairman and board in late 2005, industrial workers defied repressive rules and increasingly resorted to strikes, and university professors formed the March 9 movement for university autonomy. Egyptian physicians and engineers are mired in a dogged struggle for the right to elect their representatives, as are independent and opposition parliamentarians. As is their wont, Egypt’s ever-resourceful students took it all a step further, not simply activating moribund institutions but setting up free, functioning, parallel institutions, and bringing back the nationwide student union federation for the first time since 1979. That’s amazing, mish keda?!

There remains the thorny question of how all this sub-national democracy interacts with the national autocracy. Seems to me that the relationship is symbiotic. The mobilisation accompanying national elections can filter down to energise sub-national polls by emboldening competing forces and raising the stakes of previously marginal contests. The outcomes of sub-national elections can percolate up to the national level by providing trained cadres and spreading a zeitgeist of participation among voters. It’s also possible though not likely that there is no diffusion either up or down, and it’s probable that autocratic practices at the national level do filter down to sub-national institutions; no clearer example of this can be found than in the Mubarak regime’s placement of professional associations under government receivership to punish their electorates for their democratic choice.

Egyptian political history contains ample evidence of cross-pollination between national and sub-national elections. There are also many many examples of cross-fertilisation between sub-national elections: journalists watch carefully how judges vote, engineers watch closely how lawyers vote, everyone watches how students vote, and the regime monitors everyone and works overtime to control the representation fever gripping the population. As elections gain currency and pull in more contestants, observers, and voters, we can expect to see more struggles for associational autonomy, more hard-fought battles for associational diversity (especially among workers), more bottom-up initiatives of genuine interest representation, and in the very very long term, the democratisation of the Egyptian polity.