It’s too early to really know whether and how Egyptian politics will be affected by the latest regional armed conflict. Looking for dramatic change makes no sense, but whining that nothing will change is no better either (and more annoying). Every regional cataclysm has had an impact on domestic Egyptian politics. After all, no informed person needs to be reminded that the very character of contemporary Egyptian politics was forged in lockstep with defining regional events, specifically in the year 2000 when Hizballah drove out Israel from southern Lebanon in May and Palestinians embarked on the al-Aqsa Intifada in September.

It’s too early to really know whether and how Egyptian politics will be affected by the latest regional armed conflict. Looking for dramatic change makes no sense, but whining that nothing will change is no better either (and more annoying). Every regional cataclysm has had an impact on domestic Egyptian politics. After all, no informed person needs to be reminded that the very character of contemporary Egyptian politics was forged in lockstep with defining regional events, specifically in the year 2000 when Hizballah drove out Israel from southern Lebanon in May and Palestinians embarked on the al-Aqsa Intifada in September.The oft-heard claim that Egyptians (and all Arabs) first used to protest against Israel, then supposedly switched gears and turned their wrath upon their own governments is a myth. Domestic and regional politics have always been joined at the hip: protest against Israel was never a substitute for or a “distraction” from protest against ruling regimes. Instead, ever since the 1979 Israel-Egypt Peace Treaty and the summer 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, Arab publics and oppositions have been protesting against both Israeli policies and their own governments’ foreign policies and domestic despotism. So although it’s early, I’d like to consider two domestic consequences of Israel’s 2006 war on Gaza and Lebanon: the intensification of criticisms of the president, and renewed debate over what constitutes (and who defines) Egyptian national security.

It’s no longer shocking to ravage Hosni Mubarak in the independent and partisan press. Let’s reflect on this for a moment. In the space of four short years, from Ariel Sharon’s reinvasion of the West Bank to the American invasion of Iraq to the present, the totemic untouchability of the Egyptian president has been shattered into a million little smithereens. It’s not just a matter of biting jokes and humour, because those have been circulating since time immemorial.

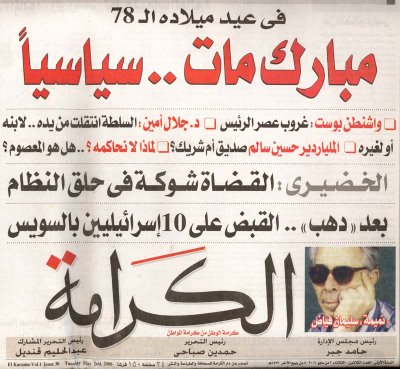

It’s a matter of holding the president accountable, as this headline from the 31 May al-Destour suggests. It’s a matter of developing serious critiques of Hosni Mubarak’s domestic and foreign policies, and questioning why the office of the Egyptian president, regardless of who holds it, should entail such stupendous prerogatives.

It’s a matter of holding the president accountable, as this headline from the 31 May al-Destour suggests. It’s a matter of developing serious critiques of Hosni Mubarak’s domestic and foreign policies, and questioning why the office of the Egyptian president, regardless of who holds it, should entail such stupendous prerogatives. To give credit where credit is due: it was al-Sha’b newspaper in the mid-1990s that started it all, with its relentless pursuit of former kingpin Yusuf Wali (remember him?) and its none-too-subtle innuendo about the shady business practices of Mubarak’s sons. The 1995-1996 battle over the draconian press law originated in the government’s attempts to silence such muckraking, and Sha’b editor Magdi Hussein served gaol time more than once after being convicted of libel. The government bided its time and then pounced when it saw its opportune moment, shutting down al-Sha’b in May 2000 when the newspaper led a campaign against Haidar Haidar’s allegedly blasphemous novel A Banquet for Seaweed.

Fast forward a decade later, when innuendo has turned into blunt criticism, and newspapers have bypassed middling cronies and reached right to the top. Hosni Mubarak and his handlers kindly helped out in this project of presidential diminishment, with their remarkable mixture of incompetence, persistent miscalculation, and extraordinary indifference to the suffering of ordinary citizens. For instance, instead of resuscitating respect in the presidency and its current occupant, the 2005 presidential elections manoeuvre was swiftly exposed for the cynical sham that it was. Not only that, but the independent and partisan press took the election spectacle as an opportunity to imagine, debate, and demand countless alternatives to Hosni Mubarak and his hapless scion. Sadly, however, the politician who came closest to mounting a real challenge now languishes in prison, a permanent reminder of how poorly the Mubarak team managed their brilliant little exercise.

When Hizballah kidnapped the two Israeli soldiers on 12 July and the Israeli military responded by destroying Lebanon, every newspaper save for those owned by the government ratcheted up its tone against Mubarak. Whereas before, pungent criticism of the president was confined to the “extremist” Abdel Halim Qandils, Ibrahim Eissas, and Gamal Fahmis, now even “respectable” university professors, doctors, and judges joined in. The issue was not so much Mubarak’s rhetorical stupidity of blaming Hizballah as his utter failure to leverage Egypt’s regional heft into pressure on either the Americans or the Israelis. And just as al-Araby led the pack during the American war on Iraq and al-Destour excelled during the presidential election spectacle, it was al-Karama’s turn this year.

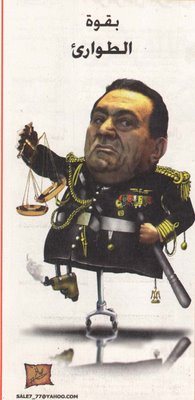

The independent Nasserist paper had been sparring with Mubarak and son since its founding last year, with biting words such as this front page of the 2 May issue, at the height of the judges’ crisis, and the blunt caricature from the same issue (top). But al-Karama dramatically upped the ante in its four most recent issues (Nos. 41-44), with blaring headlines asserting that Mubarak would be first on a top ten list of candidates for hell, speculating on whether he was guilty of treason, and averring that the first step on the road to liberation is the removal of the incumbent Arab regimes.

The independent Nasserist paper had been sparring with Mubarak and son since its founding last year, with biting words such as this front page of the 2 May issue, at the height of the judges’ crisis, and the blunt caricature from the same issue (top). But al-Karama dramatically upped the ante in its four most recent issues (Nos. 41-44), with blaring headlines asserting that Mubarak would be first on a top ten list of candidates for hell, speculating on whether he was guilty of treason, and averring that the first step on the road to liberation is the removal of the incumbent Arab regimes. Naturally, the powers that be moved to put an end to this. Last week, they dispatched the venal Safwat al-Sherif, the head of something called the Supreme Press Council that licenses and attempts to control newspapers, to complain about “certain newspapers” abusing freedom of the press to “cause offense” to the president. In a bid to divide and rule journalists, the Supreme Press Council called on the elected board of the Press Syndicate to “apply the journalistic code of ethics” and discipline al-Karama and its ilk. This has caused a serious and genuine controversy among journalists and the public, especially because there’s a good case to be made that al-Karama veered from legitimate criticism of the highest public official to an indefensible speculation on his fate in the afterlife.

It’s nobody’s business whether Hosni Mubarak is slated for heaven or hell, and I believe al-Karama erred by venturing into this distasteful, moralising territory. Yet as its editors admitted, this was a mistake, one that should not be used to abridge nor impugn the crucial right to criticise the president, his policies, and his immunity from the accountability he promised with his elections. The regime sees this as a golden opportunity to conflate the issues of legitimate criticism of the president and illegitimate attack on his person, but my conjecture is that the free press and reading public will effectively resist the pilfering of this hard-won right.

Just as the Israeli war on Lebanon abetted the ongoing diminishment of presidential sanctity, so it has opened the Pandora’s box of what constitutes and who defines national security. All three Egyptian presidents have claimed the sole right to define the national interest and decide the components of national security, and for a while society did not resist. This changed with the 1967 defeat, when the swift and devastating Israeli victory was clearly linked to the regime’s ridiculous bravado and false assurances of protecting Egyptian territory. But societal forces did not mount a serious challenge to the president’s prerogative of defining national security until Sadat's 1977 visit to Israel and address before the Knesset, when almost all organised sectors of Egyptian society rose up against Sadat’s sudden, unilateral, and enthusiastic overture to the Americans and Israelis.

Here too the president’s behaviour aided his own challengers. The professionalism and gravity with which Sadat supervised the Egyptian military’s partial victory in 1973 began to give way to disturbing delusions of grandeur. Sadat entered his Pharaoh phase, when he began believing his ridiculous rhetoric about being “the father of the Egyptian family” dispensing “the morals of the village.” So desperate was he to live up to Israeli and American flattering of him as a courageous world statesman that he scorned and then attempted to extinguish mounting domestic criticism. When Nasserist parliamentarian Kamal Ahmed hurled the epithet of “traitor” at the president in parliament, a taboo was broken and never repaired.

Hosni Mubarak inherited the strategic choices of Sadat, but not his tactics. At the beginning of his tenure, he repaired the rift between Egypt and her Arab neighbours and visibly cooled his predecessor’s enthusiasm for peace with Israel and cooperation with the United States. But despite his best efforts, challenging the regime’s definition of national security was a genie that had permanently escaped the bottle. Opposing the alliance with the United States and normalisation with Israel by definition meant criticising the Mubarak regime. Think of the heated press debates in the 1980s over the “American infiltration of Egypt,” the recurrent controversy over the role of USAID, the massive protests over Mubarak’s decision to include Egyptian troops in the American-led coalition to oust Iraq from Kuwait, the popular celebration over Hizballah’s victory over Israel in 2000, the furore over Ariel Sharon’s visit to al-Haram al-Sharif that instigated the al-Aqsa intifada, protest at the government’s decision to sell natural gas to Israel and ink the QIZ, and on and on. Underlying all these events was anger at the Mubarak government for inaction or facilitation of American and Israeli designs. Which is why I will never understand the ludicrous claim that Egyptians used to protest against Israel and America, and then started protesting against their own government.

Both Sadat and Mubarak’s definitions of national security and foreign policy centre on what they have termed “pragmatism,” that is, accepting and working with the regional status quo. As Sadat famously put it, “99% of the cards are in America’s hands.” And as Mubarak recently quipped, in answer to a reporter’s question about charting a different foreign policy, “You want me to go into the lion’s lair?” Cautious mediation and working with rather than challenging the United States and Israel are the fundaments of Mubarak’s regional stance, earning him brownie points internationally as a “moderate” Arab ruler.

But I’m hard pressed to detect anything moderate in his effusive expressions of fealty and goodwill to American and Israeli leaders. (Mubarak with George W. Bush on 4 June, 2003 in Sharm al-Shaykh, and with Ehud Olmert on 4 June, 2006 in Sharm al-Shaykh). Can you feel the love?

But I’m hard pressed to detect anything moderate in his effusive expressions of fealty and goodwill to American and Israeli leaders. (Mubarak with George W. Bush on 4 June, 2003 in Sharm al-Shaykh, and with Ehud Olmert on 4 June, 2006 in Sharm al-Shaykh). Can you feel the love?Where Mubarak and his advisers see pragmatism, critics see at best ineffective use of Egypt’s regional clout and at worst complete surrender to American and Israeli dictates. In my opinion, the most provocative and sustained critique of the Mubarak regime’s understanding of the national interest is former judge Tariq al-Bishri’s series of 2002 essays, collated in a booklet titled The Arabs in the Face of Aggression.

As with all of his ideas, bits and pieces of Bishri’s critique have been adopted by independent and opposition pundits in their commentaries on the recent war. They have characterized Egypt as no more influential than a courier, ferrying messages between the Americans, Israelis, and Palestinian officials. Hizballah’s fortitude in the face of the Israeli onslaught has once again proven Bishri’s point that the choice of “pragmatism” is just that: a choice (and an undemocratic one to boot), not the superior product of wise statesmanship nor an inevitable outcome of the regional power balance.

As with all of his ideas, bits and pieces of Bishri’s critique have been adopted by independent and opposition pundits in their commentaries on the recent war. They have characterized Egypt as no more influential than a courier, ferrying messages between the Americans, Israelis, and Palestinian officials. Hizballah’s fortitude in the face of the Israeli onslaught has once again proven Bishri’s point that the choice of “pragmatism” is just that: a choice (and an undemocratic one to boot), not the superior product of wise statesmanship nor an inevitable outcome of the regional power balance.Throughout July and August, dozens of public meetings were held, manifestoes penned, opinion pieces printed, and demonstrations organised to vocally challenge the regime’s fundamental foreign policy choices. Dozens of protest slogans, citizen petitions, and household conversations violated the American-Israeli-Egyptian government-imposed taboo on questioning existing “strategic alliances” by wondering how Egyptian national security is preserved when 1.4 million Gazans are systematically impoverished and disenfranchised, dozens of Iraqis are killed each day, and the whole of Lebanon is destroyed.

I want to single out just one out of the mounds of protest ephemera produced since 12 July: the Judges Club statement issued on 3 August, reminiscent of earlier Club resolutions such as the anti-Iraq war statement, and of course, the classic statement of March 1968. In a seven-point resolution, judges declared their “faith that popular resistance is the only path to protect the Arab nation and maintain its honour,” called on Arab regimes “to take clear positions representative of their people to dispel the suspicion that their task is to protect American interests and guard the borders of the Zionist entity,” and said that “it is no longer acceptable for Egypt to comply with the peace treaty with the Zionist enemy, after Israel has assassinated any hope of achieving peace and declared unequivocally that it will not return the land it has occupied, including Jerusalem.”

The judges concluded: “The most salient cause of this ordeal is the weakness that has afflicted the nation due to corruption and repression, evading granting Arab peoples their right to participation and self-governance by diminishing judicial independence, restricting freedoms of expression and political association, neglecting fair elections while taking care to monopolise power, and obstructing the realisation of real democracy.”

This spring, I remember that the international press was a having grand old time making heroes out of Egyptian judges and waxing poetic about their stately Club. I wonder, will they continue to do so now that it’s clear that to be pro-democracy does not mean to be pro-American, pro-normalisation, and pro-“pragmatism,” hmmmmm?

If criticising the president now knows no bounds, and challenging the regime’s version of national security is now commonplace, does this constitute a net gain for Egyptian democratisation? I think yes. Almost all regional wars have had democratising effects on Egyptian politics, meaning that they have shattered political taboos, widened the opportunities for ordinary people to make their voices heard, and increased the number and potency of popular organisations challenging or monitoring the government. The Israeli war on Lebanon and Gaza fed the increasingly adversarial press, further whittled the president down to size, and broadened debate on national security. To the extent that very little is now sacred, that we have a rambunctious watchdog press curbing and embarrassing public officials, and that basic tenets of the regime’s national security doctrine are no longer off-limits, then the war has had democratising effects.

I see no evidence and little logic to the claim that Arab democracy was the big loser in the war. Unless of course democracy is defined as being “moderate,” “pragmatic,” pro-American, pro-normalisation, etcetera. This is an influential definition, but a very rotten and disingenuous one, mish keda?

But democratic gains are fragile and not irreversible. Regime crackdowns are always possible, and imminent. American, Israeli, and Arab government campaigns to discredit their challengers as “nationalist,” “fascist,” “demagogic,” “extremist,” etcetera are always in the making. A lively, muckraking press can dissolve into shrill inefficacy if not bolstered by a professional, investigative press that asks hard questions and puts forth creative solutions to social problems. Broad public debate on the components of national security is just talk if not accompanied by effective organising that can translate into policy change. Time will tell if the latest regional war has indeed democratised Egyptian politics, and how durable and transformative those democratic gains will be.