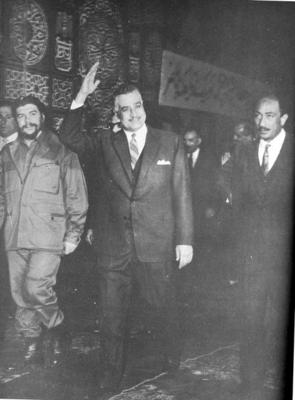

The first-ever Egyptian presidential poll set for September 7 is shaping up to be a curious exercise, a paradox where the outcome is already known but the process is full of uncertainties. In every normal election, people have their eyes trained on the result: who wins, who loses, and how things will change. In this election, however, we all know Hosni Mubarak is going to “win” (barring some miraculous deus ex machina). Yet, the process is still worth watching. Not to see the state-owned media sell the election as a token of Mubarak’s fatherly benevolence. Nor to behold Mubarak junior’s desperate attempts to sell his spent father as a real candidate with a real platform. But to follow the intense public debates on whether or not to boycott. To see the other candidates tread uncharted territory. To watch an intricate network of groups and individuals step up to monitor the poll. And to savour the ever-shifting alliances and eleventh-hour reversals within Egypt’s political class. Fifty some years ago, Gamal Abdel Nasser built the modern Egyptian hyper-presidency, dwarfing everything in sight (including the military). Anwar Sadat re-tooled it, but it took the unexceptional Mubarak to preside over its creeping diminution. Direct presidential elections are not a magnanimous nor “astute” gesture by Mubarak, but a huge, reluctant concession, one whose long-term consequences neither he nor his successors can anticipate or control. Most unwillingly, Mubarak is actually abetting the rapid deterioration of the mystique surrounding the Egyptian president. And that’s a very good thing.

The first-ever Egyptian presidential poll set for September 7 is shaping up to be a curious exercise, a paradox where the outcome is already known but the process is full of uncertainties. In every normal election, people have their eyes trained on the result: who wins, who loses, and how things will change. In this election, however, we all know Hosni Mubarak is going to “win” (barring some miraculous deus ex machina). Yet, the process is still worth watching. Not to see the state-owned media sell the election as a token of Mubarak’s fatherly benevolence. Nor to behold Mubarak junior’s desperate attempts to sell his spent father as a real candidate with a real platform. But to follow the intense public debates on whether or not to boycott. To see the other candidates tread uncharted territory. To watch an intricate network of groups and individuals step up to monitor the poll. And to savour the ever-shifting alliances and eleventh-hour reversals within Egypt’s political class. Fifty some years ago, Gamal Abdel Nasser built the modern Egyptian hyper-presidency, dwarfing everything in sight (including the military). Anwar Sadat re-tooled it, but it took the unexceptional Mubarak to preside over its creeping diminution. Direct presidential elections are not a magnanimous nor “astute” gesture by Mubarak, but a huge, reluctant concession, one whose long-term consequences neither he nor his successors can anticipate or control. Most unwillingly, Mubarak is actually abetting the rapid deterioration of the mystique surrounding the Egyptian president. And that’s a very good thing.The Candidates

The obliging No’man Gom’a. Wafd party head No’man Gom’a’s last-minute announcement that he’s entering the presidential race set pundits and politicos aflutter and was a heaven-sent gift to Mubarak. He and his regime were highly perturbed by the prospect of a showdown with Ayman Nour, but not because Nour has any real chance of winning. Nour has other obvious advantages: he’s media-savvy, young, and possesses a certain vitality that’s only been amplified by his trial fiasco. Not to mention the matter of his tacit backing by the Americans. It doesn’t really matter that he has a shady past and no name recognition outside of Cairo; he has support from all the places Mubarak cares about. As we know, Mubarak is famously averse to any hint of a competitor, and to rub salt in the wound, Nour eclipses that other fortyish pro-American secular politician: Gamal Mubarak. So when Gom’a announced his candidacy (as much to spite Nour as to assert the centrality of the Wafd), I imagine that a huge sigh of relief wafted through the presidential quarters.

Gom’a is Mubarak’s dream candidate, as much a man of the regime as an Egyptian “opposition party” chief can be. The 70-year-old Goma’ is also from Menoufiyya and went to Mubarak’s same high school. While dean of the Cairo University Faculty of Law, Gom’a was a very cooperative administrator, handing over to State Security the names of Islamist students so they could be nabbed from their homes. He was the attorney of former NDP stalwart and Agriculture Minister Youssef Wali (remember him?) in Wali’s libel battle against Magdi Hussein’s al-Shaab, helping to land Hussein and his colleagues in jail. After the death of Fuad Serageddin, Gom’a ran the Wafd like his own personal empire, alienating both lifelong members such as erudite law professor Atef al-Banna and maverick members such as Ayman Nour (kicked out of the Wafd by Gom’a in 2001). For his latest cooperative gesture, Gom’a reportedly awaits a handsome reward in the form of a “respectable” percentage of the popular vote for president, plus enough seats in parliament to ensure the Wafd become the leader of parliamentary, ehem, “opposition.”

The slick Ayman Nour. Nour’s meteoric political rise over the past nine months is in no small measure propelled by the Bush administration’s sudden interest in his profile. The American government knows that Nour’s presidential chances are nil, but that’s not the point. The point is a long-term project of cultivating a cadre of cooperative, secular pro-free market Egyptian politicians to counter the refractory Islamists and nationalists the Americans just “can’t do business with.” I’m still amazed at Nour’s transformation from a slightly sleazy, wily politico not above cutting deals with the regime to a courageous young buck ready to take on the rotten establishment, photogenic wife in tow. To read the American press, you’d think Nour was Egypt’s best and only hope for democracy. Think again. Nour is a smart and ambitious creature, indeed, but he is and has always been a one-man show.

His Ghad (Tomorrow) party, legalised last October, had the potential to be a fresh new experiment in political party-building by relatively young politicians. Instead, it’s just as personalised and leader-centred as the other cardboard parties on the scene. Who’s in al-Ghad besides Nour and his orange-bedecked and surely loyal coterie of die-hard supporters? Former MP Mona Makram Ebeid cited the same issue as her reason for leaving al-Ghad a few short months after its birth. Al-Ghad is Nour and Nour is al-Ghad; he doesn’t even pretend to delegate authority or build grassroots support. Now, I’m glad Nour is out there unsettling Mubarak and turning Gamal’s face all green, but I’m under no illusions that he has a real constituency or that he cares about much other than his own political advancement, even if it means sidling up to the Americans. The obscene anti-Nour chants of the NDP’s rented mobs and the shooting of a 19-year-old Ghad supporter in the foot are just two disturbing instances of the degree to which the regime’s people detest Nour. But let’s be clear, personalised contests between Mubarak and nemesis de jour do not a democracy make.

Gom’a is Mubarak’s dream candidate, as much a man of the regime as an Egyptian “opposition party” chief can be. The 70-year-old Goma’ is also from Menoufiyya and went to Mubarak’s same high school. While dean of the Cairo University Faculty of Law, Gom’a was a very cooperative administrator, handing over to State Security the names of Islamist students so they could be nabbed from their homes. He was the attorney of former NDP stalwart and Agriculture Minister Youssef Wali (remember him?) in Wali’s libel battle against Magdi Hussein’s al-Shaab, helping to land Hussein and his colleagues in jail. After the death of Fuad Serageddin, Gom’a ran the Wafd like his own personal empire, alienating both lifelong members such as erudite law professor Atef al-Banna and maverick members such as Ayman Nour (kicked out of the Wafd by Gom’a in 2001). For his latest cooperative gesture, Gom’a reportedly awaits a handsome reward in the form of a “respectable” percentage of the popular vote for president, plus enough seats in parliament to ensure the Wafd become the leader of parliamentary, ehem, “opposition.”

The slick Ayman Nour. Nour’s meteoric political rise over the past nine months is in no small measure propelled by the Bush administration’s sudden interest in his profile. The American government knows that Nour’s presidential chances are nil, but that’s not the point. The point is a long-term project of cultivating a cadre of cooperative, secular pro-free market Egyptian politicians to counter the refractory Islamists and nationalists the Americans just “can’t do business with.” I’m still amazed at Nour’s transformation from a slightly sleazy, wily politico not above cutting deals with the regime to a courageous young buck ready to take on the rotten establishment, photogenic wife in tow. To read the American press, you’d think Nour was Egypt’s best and only hope for democracy. Think again. Nour is a smart and ambitious creature, indeed, but he is and has always been a one-man show.

His Ghad (Tomorrow) party, legalised last October, had the potential to be a fresh new experiment in political party-building by relatively young politicians. Instead, it’s just as personalised and leader-centred as the other cardboard parties on the scene. Who’s in al-Ghad besides Nour and his orange-bedecked and surely loyal coterie of die-hard supporters? Former MP Mona Makram Ebeid cited the same issue as her reason for leaving al-Ghad a few short months after its birth. Al-Ghad is Nour and Nour is al-Ghad; he doesn’t even pretend to delegate authority or build grassroots support. Now, I’m glad Nour is out there unsettling Mubarak and turning Gamal’s face all green, but I’m under no illusions that he has a real constituency or that he cares about much other than his own political advancement, even if it means sidling up to the Americans. The obscene anti-Nour chants of the NDP’s rented mobs and the shooting of a 19-year-old Ghad supporter in the foot are just two disturbing instances of the degree to which the regime’s people detest Nour. But let’s be clear, personalised contests between Mubarak and nemesis de jour do not a democracy make.

The Debates

To Boycott or not to Boycott. Gom’a’s announcement accelerated a fascinating debate about the relative merits of boycotting the presidential (not parliamentary) election versus standing behind a consensus opposition candidate. Both sides make highly cogent arguments. Kifaya and the other myriad pro-democracy groups are pushing the boycott option as the most effective method to delegitimise Mubarak’s farcical election ploy. By refusing to help Mubarak repair his shattered legitimacy, the opposition can expose just how desperate and weak he is and further impugn his claim to rule. This would be fully in line with the pro-democracy momentum building up since last fall, based on withdrawal of consent to be governed and vocal demand for reform. I find this a particularly apposite response to what is clearly a cynical bid to extend Mubarak’s rule in democratic garb.

Yet, the other side invokes an equally compelling logic. As Salah Eissa wrote in last Saturday’s al-Wafd, the opposition should back one candidate against Mubarak as an alternative, proactive method to register opposition to the president. But I couldn’t believe my eyes when I read further down that Eissa supports Gom’a as the purported candidate and disagree with him entirely, but the basic idea is sound. Kifaya floated around this idea some months ago, and approached respected ex-judge Tariq al-Bishri as the desired candidate. If he hadn’t turned them down, we would have been faced with a truly original and exciting prospect: the unpopular Mubarak backed by the state, business, and NDP crooks, facing off with the unimpeachable Bishri backed by the Ikhwan, Kifaya, some opposition parties, and a wide swath of public opinion. Now this would have been a contest to savour: Mubarak “winning” over probably the single most esteemed intellectual and judge in Egyptian public life.

The Ikhwan’s choice. The big question now is what the Ikhwan will do. Deputy General Guide Muhammad Habib said they’re debating the issue in the group’s ranks across the provinces to decide which posture to take. The Ikhwan’s choice will be critical, and they basically have three options. Back Mubarak, and in return perhaps achieve legality, the release of jailed cadres, and a good chunk of parliamentary seats. Back Gom’a and continue the cooperation into the November parliamentary elections, especially if the government returns to the party slate electoral law. This will compel Ikhwan candidates to run on a party’s slate, and the Wafd is the only option available after the freezing of Labour (the Ikhwan allied with the Wafd before in the 1984 elections). Finally, maintain the boycott, nourish the tense cooperation with Kifaya, and focus on strategy for the parliamentary elections. Backing Nour is a remote possibility, despite news that he’s requested a meeting with General Guide Mahdi Akef. An unusual interview of Habib in the rabidly pro-Mubarak al-Gumhuriyya on Tuesday complicates any predictions of the Ikhwan’s strategy.

The Copts and politics. Another fascinating debate has erupted over controversial remarks made by Pope Shenouda III. In an interview in al-Ahram of August 1st, the Pope expressed unqualified support for Mubarak and had this to say about Kifaya, “These people would never have been so bold in previous eras, neither in Nasser’s nor Sadat’s time. So is this what this noble man deserves, he who hasn’t used his power against them?!” Pope Shenouda also dismissed out of hand the idea of a Coptic candidate for president. “The president should be of the majority religion,” he asserted. Angry reactions to Pope Shenouda’s remarks among Copts and Muslims alike have revisited the vexed question of Copts and citizenship. Most commentators are outraged at how religious figures are actively promoting Mubarak (a habit that also dogs Shaykh al-Azhar and the Mufti of the republic), belying any claims of fair coverage of all candidates. George Ishaq of Kifaya has said that the Pope’s remarks should never be binding on all Copts since he is a spiritual and not political leader, while bloggers Ramy and Africano have their own very worthwhile takes on Pope Shenouda’s incendiary stance.

Monitoring

The grassroots. In the past few weeks, several societal initiatives have sprung up to monitor the polls, mobilised by pure citizen outrage at security forces’ violence against protestors, especially on referendum day, May 25th. Most notable is Shayfeen.com (We see you), a true grassroots initiative spurred by English teacher Ghada Shahbandar, the woman who distributed the white ribbons on the June 1st Day in Black demonstration. Shahbandar and her fellow travellers are a wonderful and novel attempt at citizen vigilance; they’re purely self-funded and position themselves in support of the judges’ role. Another notable grassroots initiative is the Civil Society Coalition for Election Monitoring, coordinated by secretary-general of the Egyptian Organisation for Human Rights Hafez Abu Sa’da and bringing together eminent political scientists and writers Mohamed el-Sayed Saïd, Mustafa Kamel al-Sayyid, Hani Shukralla, Amr al-Choubaky, Nabil Abdel Fattah, and Hasan Abu Taleb. The Coalition is gearing up to monitor elections from A to Z, from training poll observers to tracking media coverage and campaign financing to compiling election-related grievances.

The Americans (and Brits?). International scrutiny of the elections is already visible and only bound to intensify. I was amused to see the British ambassador pay a visit to al-Ahram last week, inquiring of its sordid new editor-in-chief Osama Saraya how he plans to give equal time to all candidates. Please see Monday’s al-Ahram for Saraya’s incredible response. As is well known, the government is extremely leery of any monitoring efforts and has still not given a straight answer to the Americans’ injunctions to have international monitors. Perhaps in an attempt to achieve a compromise, the governmental National Council on Human Rights has announced that it is setting up an “operations room” to monitor the elections. But the United States government is not really waiting for permission. In an aggressive new policy announced by USAID director Andrew Natsios some weeks ago, money is now to go directly to NGOs without first being vetted by the Egyptian government. Sure enough, several Egyptian NGOs announced that they have received $250,000 from USAID to monitor the polls.

Additional American State Department funds are also being earmarked for a “Women’s Political Participation in Egypt” project ($350,000) and “Establishing a Network of Democrats in the Middle East and North Africa” ($750,00). The latter seeks to establish “a formal network of democrats.” What’s that, I wonder? The announcement says “training sessions” will be organised and “moral support” proffered. Capital, where can I sign up? There’s nothing I’d love more than to spend my time being recruited and educated by the American government about democracy. I say, it’s so radically thoughtful of the Americans to offer us wretched natives some training in democracy.

The Regime

Coordination woes. Managing such an election under intense domestic and international scrutiny is clearly a challenge for the regime, if only at the level of coordination. The last few months have laid bare an unprecedented degree of irresolution, backtracking, and conflicting signals coming from the powers that be, as if a window has been opened onto all their byzantine intrigues and wars of position in these exceptionally uncertain climes. Take the security response to the protests, oscillating between savage violence as on May 25 and July 30 and dovish tolerance as during the August 3 Kifaya anti-corruption protest in Opera Square, or the June 22 Youth for Change Shubra demonstration, where security forces didn’t show up at all! Is this a deliberate strategy to keep protestors off-balance or a function of lack of coordination and mutual mistrust between the Interior Ministry and the NDP’s Policies Secretariat? I’m convinced it’s the latter, fed by the Interior Minister and his underlings’ anxieties about being booted, as rumours have been percolating for weeks. The Sharm el-Sheikh attacks have further disoriented al-Adli and his henchmen and cast doubt on their basic competence.

Spin. One area where coordination seems to be marginally smoother is in media strategy. Gamal has apparently been working very hard to apply the very latest American marketing prescriptions that he worships. He’s assigned his lieutenant Mohamed Kamal to be communications chief of his father’s presidential “campaign.” Besides being Gamal bey’s dutiful errand boy, Kamal of course is the NDP’s emissary of choice to sell its “New Thought” to foreign audiences and the Arab public on al-Jazeera. Like his boss, he’s enamoured of all things American, especially the superficial variety. Kamal thinks that if he spouts politically correct terms and repeats them enough times, people will eventually believe him (and even quote him). So the point is to stay “on message,” even if the message is meaningless. Recall the pomp and circumstance surrounding talk of NDP “primaries” to select the party’s presidential candidate. Whatever happened to that? Gamal and crew’s motto is simple: talk like an American, do as you wish. The true mark of modernity, à la Gamal bey.

Rumour & Rumblings. But Gamal and Co. need a lot more than spin to get them through the next few months. All does not appear well in the corridors of power. Fresh on the heels of the Ibrahim Se’da and Osama Harb defections, rumours flew about last week regarding eternal presidential adviser Osama al-Baz. Apparently, he tendered his “resignation” but Mubarak refused to accept it, goes the story. Could the barnacle Baz be defecting? Or was he booted out? Similar stories tailed gynaecologist Hossam Badrawi, member of a purported “liberal” wing in Gamal’s Policy Secretariat who’s seen his fortunes fall precipitously over the past few months. As the ruling party crafts its strategy for the upcoming parliamentary elections, rumours are also brewing that parliament speaker Fathi Sorour (the longest-serving speaker in Egyptian history) will be shoved aside and NDP legal henchman Mufid Shehab to be put in his place. Pre-election violence in Sorour’s Sayyida Zeinab district has apparently dimmed the speaker’s chances, and his days of loyal parliamentary service are said to be numbered. Finally, the grapevine has been weighed down for weeks with talk of businessmen dispatching their capital out of the country and liquidating their assets, with certain regime stalwarts doing the same. Quite the nice little mess, eh?

Cookery. The biggest headache for the regime just now is how to engineer the outcome of the presidential vote. By how much should Hosni Mubarak “win”? Anything less than 60% would cast serious doubt on his legitimacy and offer a solid rationale for undermining his authority. Yet anything above 80% would surely strain credibility, so the magic number would seem to hover in the 70s. The trick now is how to smuggle this past the thicket of independent or American-financed monitors and intrepid judges. A subsidiary concern is how to cook up the results such that No’man Gom’a come in second and Ayman Nour dead last. In the event of a run-off after September 7, this too has to be handled delicately, and eleventh-hour surprises must be avoided at all costs. Goodness, this election business is not as easy as one would have thought. My heart truly goes out to regime strategists as they work round the clock to navigate these mines. Godspeed, gentlemen.

Legacies

Every Egyptian election year features some interesting debates, but this year is clearly different. Not because the presidency is at stake, but because for the first time the post of president is now subject to the deal-making and pitch-selling of politics, not the false veneration and above-the-fray stature of kingship. Imagine the legacies of this for the next election, and the one after that. As expressed by the most insightful observer of the Egyptian scene I know (you know who you are), something irrevocable has been set in motion, a process whose consequences we cannot fully fathom now, but a clear long-term victory for Egyptian democratic development. Mubarak and crew will no doubt make a cruel mockery of the meaning of elections this September, but the same cannot be said for 2011, or 2017. No matter who’ll be vying for the post by then, electing the president will bring him down to earth and start a process where he will have to bargain with (and be checked by) parliament, the judiciary, and societal organizations.

Manoeuvring for parliamentary elections will now be forever complicated by contention over presidential candidates, and can spill over into debate about the powers and prerogatives of the presidency itself. Already, Hosni Mubarak is adopting the constitutionalist language of the opposition, vowing to trim down and limit the powers of the president and amplify the purview of parliament in his new term. He has absolutely no intention of doing so, of course, but the fact that he feels compelled to utter such words is a startling and utterly unexpected coda to his tenure.