Forecasts of a fin de siècle fill the air, alternately breathless and reasoned. They point to the swiftly cascading natural and man-made disasters, terrorist bombings, political movement (hirak siyasi), recurring sectarian conflict, and economic malaise, all mingling in a portentous brew. Murmurs abound that Mubarak’s regime is in its final throes, that delaying local elections, swiftly renewing emergency law, and repeatedly cracking down on protest are signs of the beginning of the end. Predictably, current events are compared to the combustible final years of Anwar al-Sadat’s tenure, when the tussle between an increasingly irrational president and an angry, organised society ended so abruptly, violently, and dramatically.

Forecasts of a fin de siècle fill the air, alternately breathless and reasoned. They point to the swiftly cascading natural and man-made disasters, terrorist bombings, political movement (hirak siyasi), recurring sectarian conflict, and economic malaise, all mingling in a portentous brew. Murmurs abound that Mubarak’s regime is in its final throes, that delaying local elections, swiftly renewing emergency law, and repeatedly cracking down on protest are signs of the beginning of the end. Predictably, current events are compared to the combustible final years of Anwar al-Sadat’s tenure, when the tussle between an increasingly irrational president and an angry, organised society ended so abruptly, violently, and dramatically.There is an equally compelling though less ambient view that such predictions are facile and rather foolish. How can anyone really predict anything as complex as regime change? And even if change occurs, there’s no way to determine precisely why it happened, leaving the field wide open for every disingenuous two-bit pundit to retrospectively pronounce that he/she guessed it all along. Above all, there’s no inevitable connection between one or a few social crises and a fin du régime. Regimes have imploded in the absence of major crises or societal discontent, and regimes have survived despite multiplying crises and intense discontent. Hosni Mubarak’s regime has been dogged by crises and intensifying street protest since at least 2000, yet it totters on.

Déja Vù

I remember the same feeling of an untenable status quo on the verge of explosion. It was in spring 2003. As the American invasion of Iraq was imminent, the government speedily secured the renewal of emergency law. Massive anti-war protests then shook the country, and biting anti-Mubarak slogans electrified the streets. Security forces viciously beat protestors and threatened the women among them with rape; two opposition parliamentarians were savagely attacked by hired thugs; Hosni Mubarak’s obscenely huge visage was torn off the NDP headquarters, and Gamal Mubarak “led” a hastily organised government anti-war protest in Cairo stadium, flanked by the bankrupt and sycophantic Adel Imam and the erstwhile powerbroker Kamal al-Shazli (those were the good old days, Kimo. How cruel are the times).

Back then, Abdel Halim Qandil (right) and Abdellah al-Sennawi took turns savaging the regime, and with considerable rhetorical force, too. It was difficult to resist their weekly forecasts of impending doom, of a spent regime devoid of any ounce of legitimacy, stupidly hastening its own ignominious demise. When several presidential emissaries failed to tame the intrepid duo, Qandil was plucked from his Cairo street in the dead of night and stuffed into a speeding car by four massive individuals in suits. They savagely beat him, demanded that he stop writing about “the big people,” stripped him of all his clothes, and left him to die on a deserted highway on that frigid November night. Of course, this only widened his popularity and fortified his resolve, earning him the respect he deserves. As for Sennawi, he continues to tirelessly deliver weekly auguries of regime downfall, apparently untroubled by plenty of evidence to the contrary.

Back then, Abdel Halim Qandil (right) and Abdellah al-Sennawi took turns savaging the regime, and with considerable rhetorical force, too. It was difficult to resist their weekly forecasts of impending doom, of a spent regime devoid of any ounce of legitimacy, stupidly hastening its own ignominious demise. When several presidential emissaries failed to tame the intrepid duo, Qandil was plucked from his Cairo street in the dead of night and stuffed into a speeding car by four massive individuals in suits. They savagely beat him, demanded that he stop writing about “the big people,” stripped him of all his clothes, and left him to die on a deserted highway on that frigid November night. Of course, this only widened his popularity and fortified his resolve, earning him the respect he deserves. As for Sennawi, he continues to tirelessly deliver weekly auguries of regime downfall, apparently untroubled by plenty of evidence to the contrary.Old but Sturdy?

If Mubarak and his retinue survived the upheavals of 2003, which were arguably the gravest challenge to their rule, then why shouldn’t they be able to muddle through the current difficulties? The regime is still intact, internal fissures exist but are manageable, and there have been no spectacular defections of any key pro-regime figures or blocs. The ministers are all siphoning off our public funds and tying up traffic as usual, governors are slavishly doing their jobs as glorified security personnel, and NDP independents are kept in line and are only really troublesome during elections.

The ballyhooed “reformists” surrounding Gamal Mubarak are busy walking their delicate tightrope of just the right amount of loyalty coupled with a healthy helping of, shall we say….flexibility. The hubbub manufactured by the unctuous Osama Ghazali Harb a few months back was an amusing but essentially harmless little sideshow. Much as he clambered to claw his way into the inner circle, Harb was never more than a pathetic, marginal hanger-on, perpetually pleading and grovelling at the gates, only to be unceremoniously rebuffed every time. So he finally grew tired and embarked on his latest project of reinvention. Mr Harb is apparently contemplating founding a “liberal” political party with other “respectable” social personages.

As the truly great Stefan Rosti (centre) used to say, “diabolical!” (gahannami!).

As the truly great Stefan Rosti (centre) used to say, “diabolical!” (gahannami!).If the commanding heights of repressive rule are holding together, so seem to be the nuts and bolts. The enforcers of repression continue to follow orders and to smash dissidents. Everyone from governors to security directors at the top to police chiefs, officers, and simple recruits at the bottom are doing their bit (if not more) to run the coercion machine. If anything, it seems as if the new Cairo security chief, Ismail al-Shaer, is even more ruthless than his predecessor Nabil al-Ezabi, who’s moved on to greener pastures. For his efforts in policing the numerous contentious episodes of 2005, Ezabi has been rewarded with a big, fat governorship (mabrouk ya siyadat al-liwa).

For the regime to end, state security personnel must splinter and some then join the reform movement, even if secretly à la Ukraine. At the very least, a critical mass must shirk their duties and withhold their cooperation. Everyone was excited by the 1986 CSF mutiny precisely because it seemed as if the agents of repression were turning on their masters, at a time when other social forces (particularly labour) were also rebelling. But the formidable capacities of the Egyptian state effectively contained that brief upsurge, and draconian new control mechanisms were instated to prevent any second acts. If the sinews of state control remain intact and loyal to the regime, it’s difficult to imagine how the latter can be dislodged.

Much has been made of the security forces’ crushing of protestors over the past few days, and at least one person has written that the culture of police brutality and impunity is itself a portent of impending chaos. However, aside from the one incident of the police beating of judge Mahmoud Hamza on 24 April, recent police brutality is nothing new. Has some invisible threshold been crossed?

What of the most inscrutable institution in Egyptian politics? There’s a lot of talk about what the military will and won’t do in X, Y, or Z event, but frankly, I don’t know how anyone can credibly claim to know anything about the potential behaviour of this institution. I don’t care how many “Western diplomats” are anonymously quoted in foreign news accounts pontificating on this matter. Nor how many informal conversations were had with “top-ranking generals” while strolling on the beach at Marina (or is it Ain al-Sukhna?). Or any of the other laughable gossip and tall tales that enliven the cocktail party functions of the foreign and local blathering classes. Some Nasserists seem to think that the valiant military will step in at just the right moment to prevent a handover of power to Gamal or to save Egypt from other nightmarish prospects. I beg to differ. If this logic holds, the military would have stepped in a long long time ago, mesh keda walla eih?

The most intriguing thesis I’ve heard (and wish I could claim credit for) is that the military no longer acts as a coherent, corporate entity. Since the Abu Ghazala affair, Hosni Mubarak has ironically presided over the comprehensive depoliticisation of the Egyptian military. Although he does not explicitly make this argument, the most astute and respected scholar of Egyptian organisations had this suggestive yet still crucial information to share on current military practices, facts that have gone strangely undiscussed. Anyone who claims that the military can still act as the final arbiter and guardian of the republic must contend with both severe lack of information and internal organisational practices that suggest quite the opposite.

The End Draws Nigh?

If there are very good reasons to doubt forecasts of imminent regime demise, there are equally good reasons not to uncritically accept assertions of regime “stability.” After all, no serious observer can dismiss the significant, perhaps seismic shifts over the past few years in how the regime interacts with its domestic and international interlocutors. A regime that was able to effectively quell a militant Islamist insurgency from 1992-1997 now seems unable to manage peaceful voters, peaceful judges, and peaceful street demonstrations.

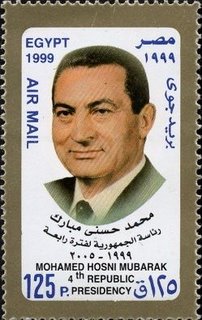

A regime that convinced the country and the world that it was waging a brutal but necessary campaign to rid Egypt of terrorism now cannot muster a single convincing explanation for any of its increasingly irrational and often hysterical actions. In September 1999, Hosni Mubarak began his fourth term with only the faintest murmurs of elite opposition, confined to closed rooms and abstruse constitutional conversations at that.

In September 2005, Hosni Mubarak was being pilloried and humiliated in public and private just as he was putting himself up for "election" (AP Photo, September 10, 2005).

In September 2005, Hosni Mubarak was being pilloried and humiliated in public and private just as he was putting himself up for "election" (AP Photo, September 10, 2005).The signs of decay are numerous and multiplying all around us, but in my opinion, two in particular stand out as indices of a potential cataclysmic upheaval. First is the extent to which Hosni Mubarak and especially his family have become the target of popular hatred, biting ridicule, or mild distaste (depending on who you talk to). There is no disaster, policy decision, or daily inconvenience that is not popularly believed to originate at the doorstep of the presidential residence. Whether it’s the series of tunnels and overpasses near Heliopolis and Madinat Nasr, or the fancy, air-conditioned “capital cabs” complete with digitised meters, or the crackdown on opposition candidates and voters during elections, or the crackdown against alleged homosexuals, or the decision of the Minister of Justice to refer two senior judges to a disciplinary board, it is truly remarkable how swiftly such actions are attributed to Gamal, Alaa, and Suzanne Mubarak, by both patrician and plebeian alike.

It matters little whether these and other decisions are actually the work of the ruling family. What matters is the near-unanimous public perception, the incessant jokes, the rich rumours, and the flourishing samizdat. If Suzanne Mubarak is continuously presented to us as the First Lady of Virtue and Beneficence and her son is foisted upon us as the Visionary Young Moderniser with a Heart of Gold, is it any wonder that Egyptians believe the president’s family runs the country? Add to this additional tangible facts such as the yawning succession vacuum, the marriage between business and power (of which the ruling family is a neat exemplar), and the never-missed opportunities to exploit and insult Egyptians.

I cannot contain my outrage at this last trait. When the ferry sank and the Dahab bombings happened, the state-owned media made sure to highlight that Gamal bey’s “Policies Secretariat” observed a moment of silence for the ferry victims, and Suzanne Mubarak oh-so-graciously cancelled her trip to a “businesswomen’s conference” in Turkey so she could visit the Dahab injured. Does this not reveal an extraordinary level of indifference to the loss of human life and to the grief of family members? (Family members of ferry victims, Cairo, March 13, 2006).

I cannot contain my outrage at this last trait. When the ferry sank and the Dahab bombings happened, the state-owned media made sure to highlight that Gamal bey’s “Policies Secretariat” observed a moment of silence for the ferry victims, and Suzanne Mubarak oh-so-graciously cancelled her trip to a “businesswomen’s conference” in Turkey so she could visit the Dahab injured. Does this not reveal an extraordinary level of indifference to the loss of human life and to the grief of family members? (Family members of ferry victims, Cairo, March 13, 2006).If the ruling family is increasingly viewed as the problem, an unlikely sector is increasingly viewed as the solution. The second sign of regime decay is the Mubarak regime’s unexpectedly drawn-out and now extremely public confrontation with judges. This could have remained a contained and rather marginal intra-state affair, were it not for the highly unusual and intensifying public support of judges as the only trustworthy, inspiring, and capable force in public life. Every major pundit has written about the judges’ saga over the past two weeks. Nearly every major social group has visited the Judges Club to express solidarity for the ongoing sit-in. And as we know, the extremely brave and committed young activists who have staged their parallel sit-in supporting the judges were attacked three times by security forces and finally forcibly removed one day before Bastawisy and Mekky’s hearing.

That day was a turning point of sorts. The outpouring of public support for judges on 27 April took everyone by surprise, most of all the judges themselves. It surpassed the solidarity demonstrations of 13 May, 14 August, and 2 September 2005, and it surpassed the turnout on 17 March 2006. As a judge and member of Bastawisi and Mekky’s defence team reflected, “One amazing thing is that on our way from the Club to the courthouse and back, security failed completely and we were hugged by the masses, they knew us by name, they were singing for us, one of them kissed my hand! It was a huge day in the history of our country, I know that our days will be dearly remembered as part of our great history for years to come, thank God I was part of it no matter how small, and thank God I was on the right side.”

An intriguing proposal was floated on that day, first by Nasserist parliamentarian Hamdeen Sabahy in the library of the Cassation Court, as throngs of judges, journalists, and lawyers waited for the disciplinary board’s verdict (adjournment until 11 May). He said that if the two judges are dismissed, Egypt will have gained two candidates for president. The electrifying suggestion was met with enthusiastic applause and of course percolated to high places. The authorities are reportedly now scrambling to contain the whole matter before 11 May.

The Judges’ Club resolution after its 27 April emergency general assembly is a powerfully worded document. Its last paragraph in particular has a momentous ring to it, at least for me: “Egypt’s judges, and they represent one branch of state power, realise that the nation is the source of all powers, and that achieving security and stability has it source in the prosperity of the nation and the consent to its rulers, and that the rulers’ esteem is in responding to the desires of citizens, not in haughtiness and intransigence. There is no way of achieving security and stability in the country merely through the repression of force and the control of power. Rather, the people’s hope in justice must be preserved, as well as preserving their dignity and honour, and reviving their hope in reform, and establishing a true democratic life through fair elections and real transfer of power, and lifting all exceptional laws including ending the state of emergency, and unleashing freedom of expression, and the freedom to form parties, unions, and associations, without any restrictions, so that Egypt can regain its place among nations.”

Aporia

There are firm grounds for confidence in regime stolidity, and equally robust signs of impending implosion. Comparing current events to the twilight of Sadat’s rule or Hosni Mubarak to Romania’s Ceauşescu is good for dramatic effect, I suppose, but I wonder how those comparisons are made, and to what extent they are simply parroting a currently very trendy idea. I am also confounded by those who think that nothing has changed, who dismiss popular ferment as so much frippery that doesn’t dent the “real” sources of power, who assert that only external pressure matters.

There are firm grounds for confidence in regime stolidity, and equally robust signs of impending implosion. Comparing current events to the twilight of Sadat’s rule or Hosni Mubarak to Romania’s Ceauşescu is good for dramatic effect, I suppose, but I wonder how those comparisons are made, and to what extent they are simply parroting a currently very trendy idea. I am also confounded by those who think that nothing has changed, who dismiss popular ferment as so much frippery that doesn’t dent the “real” sources of power, who assert that only external pressure matters.I think only an oracle (if there are such things) can know which “path” will be trod at this “crossroads” that so many people keep announcing. If Egyptian politics have indeed arrived at a crossroads, then I’d like to savour the extraordinary uncertainties and hence possibilities that characterise such points. Unless you’re Teiresias, loud assertions about the likelihood of this or that “scenario” are rather dubious, mesh keda?

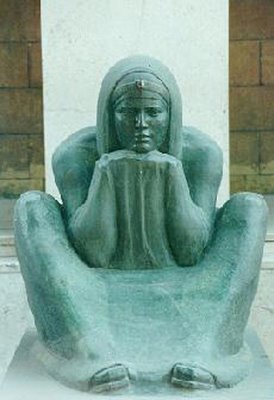

*Mahmoud Mokhtar, “Keeper of Secrets” (Katematul Asrar)