Commentary on Egyptian Politics and Culture by an Egyptian Citizen with a Room of Her Own

Tuesday, May 31, 2005

Thank You

I’m moved by your plea to open up to comments and debate. I understand that it’s motivated by concern and appreciation, and that humbles me. Thank you for caring enough to read my thoughts and to write this eloquent missive. Ashkurak ‘ala husn al-qira’a.

Blogging for 3 months has been exhilarating, exhausting, time-consuming, but above all enlightening. I started it to clarify my thoughts, in line with one of my favourite quotes, said by someone famous whose name I don’t remember now: “I write to discover what I think.” But in the process of figuring out what I think, I’ve also learned about what other Egyptians and Egypt-watchers think, and that has been extremely edifying for me.

Having one’s ideas resonate with others is the most gratifying feeling for a writer, and I want to take this opportunity to send a heartfelt thanks to each and every person who takes the time to read this blog, and/or to e-mail me, and/or to link to me. A special word of thanks to the generous Abu Aardvark (and no, he’s not my agent and I don’t pay him to link to me). I especially thank everyone who’s e-mailed to say how and why they couldn’t agree less with me. I’ve received many such thoughtful e-mails, and I do my best to reply to each one. Thank you all, very much.

ChaösGnösis, I understand the impulse behind your plea to include comments, and I cannot disagree with it. But I’ve thought plenty about it, egged on by the prodding of friends and relatives and your own letter, and at bottom I can’t really explain my resistance to comments. The reason I shared with you is definitely true: the blog takes up too much of my life already, and opening up to comments would only increase the time I spend in front of the damned monitor, and my eyes and real job just can’t handle that. But I admit that my resistance has a non-rational basis as well. I’m old-fashioned and see this blog not as an interactive forum but my little ‘zine, and those who are so moved are welcome to e-mail me comments. Following my own rules, I also don’t comment on others’ blogs.

I’m truly sorry if this disappoints you, but at the same time I know you’ll understand. Let a thousand different styles bloom.

I don’t want to fall prey to the conceit that bloggers can change Egypt; I don’t even think that’s the right question. But I do feel less isolated by being a part of this new community of online diarists. I love Beyond Normal’s humour and insight, and Wa7damasrya’s commitment and eloquence, and FromCairo’s integrity, and Digressing’s sagacity, and Hamuksha’s creativity, and Samia’s whimsy, and Wandering Arab’s dark humour, and Perplexed’s measured outrage, and Cinematographe’s graphic outrage, and Rehab’s individuality, and The Arabist’s multivocality, and Orientalism’s painstaking photo narratives, and ChaösGnösis’s Rumi-love, and Socrates' perspicacious poetry. You’ve all delighted and unsettled me, and I hope I’ve done the same for you.

The above are just a smattering of my favorite blogs, the entire list is here, thanks to mindbleed, and the wonderful Manal and Alaa maintain the feed. At the very least, we all prove Egypt’s diversity and decency, against the naysayers and prevaricators and ignoramuses and pimps, who would have us believe that we’re a nation of ingrates, political adolescents and worse, such is the debased quality of their public rhetoric. I started blogging because they make me angry, and I continue blogging because they want to erase and falsify Egyptian history and deny Egyptian democracy.

The Egyptian deity Theuth argued that the written word “will make the Egyptians wiser and give them better memories,” but Plato derided writing in favor of dialogic discussion and interaction. I respect and agree with the Platonists, but for now remain wedded to Theuth’s words.

Here's to an independent, just, and democratic Egypt,

Baheyya

Remember them

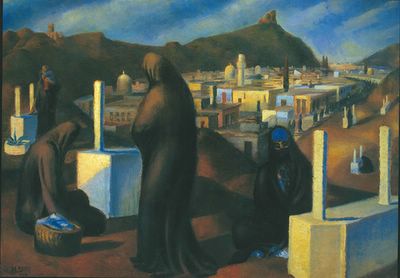

Mahmoud Said's "Motherhood" (1931)

When I saw the pictures of assaulted women last week, I thought of the thousands of other abused women whose stories we don’t know, the thousands of broken families, fatherless children, impoverished households, and heartbroken grandparents whose grief we can never console. All of it courtesy of the predatory police forces of Hosni Mubarak’s regime, whose raison d’être has become the literal violation, maiming, and killing of ordinary citizens. As we don black today to condemn the crimes of 25th May, let’s also remember the crimes of Mays past. Remember the fallen mother of four who died at the hands of police in March: Sarando’s Nafisa al-Marakbi, 38, whose spirit expired shortly after her body was violated by criminal police agents.

It is a testament to the resounding failure of the Mubarak regime that the one day it set aside to trumpet its democratic credentials to the world instead turned into a domestic and international scandal, a fadiha par excellence. The referendum will forever be remembered as the day the regime hit rock bottom, as novelist Alaa’ al-Aswani writes in al-Araby. The deliberate and methodical targeting of women demonstrators under the gaze of policemen, detectives (such as they are), and even more high-ranking employees of the Ministry of the Interior was dismissed as “exaggerated” by the president’s spokesman. By that warped logic, more women and men had to be assaulted before the powers that be deem the event serious enough to warrant mention.

And yet, and yet, it behooves us to remember that the 25th May scandals were not unprecedented.

Recall the March 2003 anti-Iraq war protests, when a supremely nervous regime faced off with a spontaneously outraged and mobilised society. The events of that spring now appear eerily like a dry-run for today’s upheaval. Women protestors were dragged on the street by the hair, beaten, and hauled off in paddy wagons where they were threatened with rape by Interior’s officers. Members of parliament Hamdeen Sabahy and Muhammad Farid Hasanein were viciously beaten and detained. Journalist Ibrahim al-Sahari was snatched from his bed in the dead of night. Seasoned (and aging) activists Ashraf Bayoumi and Abdel Mohsen Hammouda were roughed up and detained, despite peacefully demonstrating at Sayed Ayesha square with permissive court ruling in hand. It was as if the regime was saying: nothing is sacred. Not the sanctity of women’s bodies, nor parliamentary immunity, nor the prestige of the fourth estate, nor the shield of old age. It was but a short leap to the events of last week (though let’s not forget the November 2004 attack on al-Araby editor Abdel Halim Qandil in the interim).

Back then too, society fought back, sending defiant messages to “Interior’s floggers” of “we are not afraid.” Putatively apolitical wives sent out eloquent open letters ennobled by grief and courage. Human rights lawyers motioned to sue Mubarak and his Interior Minister in the courts. And even our hapless parliamentary representatives mustered enough outrage to condemn the assault on their institutional if not political colleagues. The street was ablaze. Hosni Mubarak’s ridiculously large poster was torn off the NDP headquarters; faculty stirred alongside wrathful students on campus, the unions of the professions played their historically conditioned roles, and the seeds of bitterness and anger were sown into the souls of ordinary citizens who felt helpless and ashamed at their government’s acquiescence to American writ. Those resonant anti-Mubarak slogans were coined that spring, when the first, tiny anti-tawrith demo made its voice heard in front of the People’s Assembly.

If we want to be honest with ourselves, then we cannot claim that the state-sanctioned targeting of women on “black Wednesday” 2005 was unprecedented. The Mubarak regime has a long record of distinction on that front. How many relatives of Islamist detainees were beaten, raped, impoverished, and otherwise immiserated by security forces since 1992? If conservative estimates put the current number of detainees in prisons without trial at 16,000, I’m sure you can appreciate the magnitude. It did not all begin with the Taba bombings of last October, either, those were but the most visible tip of a huge, submerged and horrifying iceberg.

There is an entire subculture of invisible citizens in this country with first-hand experience of the state’s ferocity. There are dozens of wives, mothers, sisters, and sisters-in-law who were beaten, stripped naked, and raped by police officers, sometimes in front of their detained husbands and/or children. There are dozens of pregnant women who miscarried due to torture. There are dozens of haunted women with scarred souls and violated bodies whose stories we don’t know. There are dozens of haunted men with scarred souls and violated bodies whose stories we don’t know. Would that we remember and honour them too today.

Novelist Alaa’ al-Aswani helped to mainstream the issue of state torture of Islamist detainees in his novel ‘Imarat Yacoubian. A prior and even more harrowing and powerful work is Magdi al-Batran’s fictionalised account of his tour of duty in Egypt’s south, Yawmiyyat Dhabit fi-l-Aryaf (Diary of a Police Officer in the Countryside, 1998). With a tortured conscience and a matter-of-fact style, al-Batran reveals the unspeakable state abuses against Egypt’s most vulnerable citizens in the mid-1990s.

I spent a somber afternoon reading through the painstaking reports of the EOHR and Muhammad Zarie's Human Rights Association for the Assistance of Prisoners (HRAAP), with their damning and heartrending details of systematised state violence against men, women, children, and the elderly, violence that now routinely ends in loss of life. Please read what has become of us at the hands of this predatory regime. And especially, read the missives of parents of detainees to the right honourable Interior Minister, appealing to his fatherly instincts when all else fails, hoping against hope that his heart may perchance be as tender as their own. It is not for nothing that the EOHR a few years ago dedicated Mother’s Day to the thousands of mothers of perpetually detained sons.

Out of the dozens of tragic stories in the rights groups’ reports, two haunt me. The mother of detainee Zaki al-Sayed Suleiman, 25, and held in Fayyoum prison, recounts:

Last Eid, good Samaritans told me that the government would allow the families of detainees in Fayyoum prison to visit on the first day of Eid. I was so happy, I haven’t seen my son in years, and I bought everything I could for him. After waiting for four hours in front of the prison gates, they told me visits weren’t allowed for political prisoners. I said to them, aren’t they human beings too? And I cried and pleaded with them to let me see my son, that I only wanted to greet him for the Eid, but they refused (HRAAP, “Kingdom of Silence: For Security Purposes, Four Prisons Closed,” 1999).

Suad Mohamed Hasan, the mother of Safieddin Hussein Hammoudi, 32, detained since 1996, recounts:

I am 60 years old. My only son was arrested on November 13, 1996; before his arrest he worked as a teacher. Since his arrest, I live alone in the house in Naga’ Zureiq village, Markaz al-Badari, Assiut governorate. I asked after him and learned that he was in Fayyoum prison. I tried to visit him and learned that visits are forbidden to Fayyoum prison. Since the date of his arrest, I have not seen him and he has not attended the wedding of his only sister. I sent several complaints to the President of the Republic, the Interior Minister, the Attorney General, the speaker of the People’s Assembly and the President of the Shura Council and the Secretary-General of the National Democratic Party asking for the release of my son and only supporter, as well as permitting me to visit him…since no convictions were issued against him and he has obtained several orders of release, or granting me power of attorney so I can access his salary from the Ministry of Education, and I haven’t received a response until now (HRAAP, “Kingdom of Silence: For Security Purposes, Four Prisons Closed,” 1999)

I am forever grateful to the staff of these human rights organisations for collating these materials, so that at the very least, we may never forget. And today, I am grateful to the indefatigable and proud Manal and Alaa for culling a valuable 47-page documentary record of the abuses during the 25th May referendum (PDF here).

When I saw the pictures of assaulted women last week, I thought of the thousands of other abused women whose stories we don’t know, the thousands of broken families, fatherless children, impoverished households, and heartbroken grandparents whose grief we can never console. All of it courtesy of the predatory police forces of Hosni Mubarak’s regime, whose raison d’être has become the literal violation, maiming, and killing of ordinary citizens. As we don black today to condemn the crimes of 25th May, let’s also remember the crimes of Mays past. Remember the fallen mother of four who died at the hands of police in March: Sarando’s Nafisa al-Marakbi, 38, whose spirit expired shortly after her body was violated by criminal police agents.

A day in July 1997, 10 am. The pleasantly draughty corridors of Detainees’ Affairs, tucked away discreetly at the back of the Shari’ al-Gala’ court complex. A hole-in-the-wall makeshift “cafeteria” dispenses scalding tea and packets of brittle butter biscuits with the rippled edges. Rural families sit huddled on the floor surrounded by their humble belongings, looking down wearily with the gait of weeping willows. Surly clerks gossip and remain impervious to the unlettered supplicants. A dark-skinned woman clad in black with a round, kind maternal face moves from office to office in search of the whereabouts of her imprisoned son, who is constantly transferred from prison to prison by authorities without notifying his family. “First they told me Wadi el-Gedeed, then Fayyoum, then Tora; I make the trip up from the south every week and I still haven’t seen him, he’s been inside for five years.” She stops briefly and allows herself the tears she’s held back for so long. Then she collects herself, wipes the tears with the edge of her black tarha, shrugs off the offer of tea, and firmly walks the steps traced by the prophet Job.

Sunday, May 29, 2005

Call from the Association of Egyptian Mothers

Egypt Wears Black, Wednesday 1 June 2005

The Association of Egyptian Mothers (Rabetat al-Ummahat al-Misriyyat) has circulated this call via e-mail, and it's swiftly making the rounds of the Egyptian blogosphere; the Arabic original can be found at Rehab's. Thanks to Alif for the photo. This is my verbatim translation.

All of Egypt Will Wear Black on Wednesday, 1 June 2005

On 25 May, the day of the referendum, women and girls participating in peaceful demonstrations demanding democracy in Cairo at the Press Syndicate were subjected to harassment and sexual assault in public, perpetrated by simple people rented by thugs of the National Democratic Party and supervised by generals of the Interior Ministry.

We the Egyptian Mothers who dream of a better future for the homeland and a better life for our children have decided to invite the Egyptian people to leave their homes as usual next Wednesday, the 1st of June, but wearing black on their way to work or while running their daily errands.

As for activists, we call on them in all of Egypt’s provinces to coordinate peaceful, silent vigils in front of their syndicates or in their universities or in certain public places they agree on, in silence and complete solemnity in their black clothes.

The Egyptian Mothers is not a political movement, it is the voice of the silent majority of women, housewives and working women. But they have realised today that the Interior Ministry has overstepped all red lines, and that silence today is a crime and we must stand up in united formation as a united people to defend the Egyptian woman and girl.

Our demand is clear, it is a single demand: the resignation of the Interior Minister.

All of Egypt will wear black in silence on the 1st of June, from the extreme North to the extreme South, its men, women, youth, and aged people, sadness in its streets and a wound in its heart. The people’s demand is simply the resignation of the Interior Minister. We have stood by watching for a long time, but we have decided to go out next Wednesday, for the first time, in defense of the honour of Egypt’s women citizens, women and girls, in police stations and on the street and in demonstrations.

On the 1st of June, all of Egypt will be dressed in black, for the sake of our daughters who were assaulted and had their clothes torn in the street because they dared to say enough instead of remaining silent. We will go out this time (and we are not from the Kifaya movement) to tell Interior whose role it was to protect us: the game is over.

A day of silent popular mourning and a single demand: the resignation of the Interior Minister.

Afterwards, we will either return to our homes and our daily lives, in the way of Egyptian women and their familiar struggle for their daily bread, family, and children since the dawn of this civilisation and throughout the history of this peace-loving homeland, or we will think of a next step if our demand is not met.

We emphasise that we are not from the Kifaya movement and do not belong to any political force, legal or otherwise. But when the Egyptian woman pays the price of her political participation with the sanctity of her body and her honour, then every Egyptian mother and all of Egypt will go out in clothes of mourning to tell the Interior Minister:

We want your resignation…today…now.

We will see you all on Wednesday, the 1st of June, a normal day, in our black clothes, calmly, and in bitter silence, for the sake of a free future.

Saturday, May 28, 2005

The Guild Society

Wafd Party Women's Committee, al-Musawwar, 13 March 1925.

When Ahmed Nazif, our inept Prime Minister who doubles as a doormat, claimed that Egyptians lack the requisite maturity for democracy, it was not a gauche slip of the tongue but a well-rehearsed staple of the ruling NDP’s “New Thought” (Fikr Gedeed). “New Thought” has more than a whiff of agitprop; it is the centerpiece of the NDP’s facelift after the 2000 elections, the ideational armature that has smoothed Gamal Mubarak’s meteoric political rise.... I consider it beneath me to dissect the NDP’s new “ideas” but I note: these spurious claims are being recirculated just as Egyptians are rising up to demand their rights. And I seek refuge in the inconvenient truths the theorists of “New Thought” work assiduously to distort and falsify. What I want to show here is not that Egyptians are ready for democracy; that would be accepting the stupid and racist premises of the NDP’s fourth-rate intellectual apologists. Instead, I want to wade through some Egyptian history for the organisational roots of the intifada we’re seeing this year.

***********************************************************************************

With their luculent demands for free elections and professional autonomy, Egypt’s judges have rightly captured the world’s attention and fired up the imagination of Arab democrats; Lebanese commentators have started a debate on their own judicial institutions (see an-Nahar of 19 and 25 May). Egyptian judges’ measured mobilisation also calls attention to the incremental but steady reawakening of Egypt’s other corporate groups: students, workers, journalists, lawyers, engineers, university faculty, even Sufi orders, even if these latter came down in favor of Mubarak.

Novelist Ibrahim Abdel Meguid is hoping that Egypt’s Writers Union will hop on the reform bandwagon (though good luck with Mohamed Salmawy as president). Egypt’s big businessmen are absent from the picture, probably too busy worrying about where to put their assets in the event of regime change, so tied are their fortunes to the fate of the Mubarak presidency. Egyptian businessmen are diffident democrats, to put it very generously. They’re perfectly fine with autocracy if it protects their right to make money. As for Egyptian workers, the most thoroughly muzzled corporate group, their reform stirrings have been perforce more muted, save for one notable protest on 7 May.

How can we explain this associational effervescence on the Egyptian scene? As usual, it’s propelled by a mixture of propitious opportunities and inherited organisational experience. It mimics notable moments in contemporary Egyptian history: 1919-22, 1946-1952, 1968, 1977-81. It carries within it the spectacular successes and crippling contradictions of those resonant turning points. It is also the most effective rejoinder to an avalanche of stale, sinister notions that are a persistent undercurrent in Egyptian public debate. Let’s look briefly at what these look like, and where they’re coming from.

The gurus of "New Thought", a cackle of presumptive “political scientists” headed by Alieddine Hilal and headquartered in the once-respected Cairo University Faculty of Political Science and the Ahram Strategic Studies Centre, proceeded to advance the view that Egyptians are not prepared for democracy, but must first acquire the requisite democratic culture and “values” before getting a taste of the sweet elixir. “You can't have democracy without democrats. You cannot have democracy imposed on authoritarian societies,” said Hilal (New York Times, 3 October 2002), back when he was Youth Minister before being booted in last July’s reshuffle (Pity, was Gamal not pleased with the performance of Dr. Hilal?).

In a speech on July 26, 2003, Hosni Mubarak claimed that democratising all at once is like offering liters of water to a parched man; he will die (al-Ahram, 27 July 2003). Better to introduce democracy in doses, to be determined by the self-appointed guardians of the Egyptian people: the Mubarak government and its allies, of course. Last week, Laura Bush kindly pitched in with her own theory of democracy, to buttress the intellectual exertions of the “New Thinkers”: “You have to be slow as you do each of these steps…You know that each step is a small step, that you can't be quick. It's not always really wise to be, but I'm very, very happy with the idea of an election here in -- a presidential election, and I think he's been very bold and wise to take the first step.”

I consider it beneath me to dissect these ideas, not least because it places undue strain on my sanity and fouls up my mood. Instead, I note: these spurious claims are being recirculated just as Egyptians are rising up to demand their rights. And I seek refuge in the inconvenient truths the theorists “New Thought” work assiduously to distort and falsify. What I want to show here is not that Egyptians are ready for democracy; that would be accepting the stupid and racist premises of the NDP’s fourth-rate intellectual apologists. Instead, I want to wade through some Egyptian history for the organisational roots of the intifada we’re seeing this year. Ours is a country rich in associations, orders, guilds, and syndicates. Belying false models of Egyptian history as a tale of a gargantuan state preying on a prostrate society, or an enlightened state leading an immature society, Egyptian history is full of stories of associational activism and spirited, organised sparring with the state. If you want to believe Egyptians aren’t ready for democracy, I feel sorry for you. If you want to understand the historical roots of what’s happening today, I hope this story will engage you.

A masterful new study unearths this fascinating period of Egyptian history, when the sturdy guilds came apart under the twin assaults of state control and Egypt’s integration into the world economy. Mining the documentary gems in Dar al-Watha’iq, John Chalcraft’s wonderful The Striking Cabbies of Cairo and Other Stories (2004) traces the process of guild transformation into modern trade unions in the 19th and 20th centuries, complete with fascinating stories of petitions and protest by Cairo’s cabbies, Boulaq’s carters, Port Said’s coal heavers, and Alexandria’s porters.

As we know, the latter half of the 19th century was an incubator for all sorts of organisations, plebeian and patrician alike. As the Europhile Khedive Ismail was energetically bankrupting Egypt in his quest to turn it into a piece of Europe, Egyptians were coming together in a dizzying array of associations. Masonic clubs shared social space with cultural salons, philanthropic societies, workers’ fledgling unions, and secret societies. Associationalism was tinged with all sorts of ideological hues: Islamist, constitutionalist, nationalist, nativist, and everything in between. Membership consisted of Egyptian Muslims, Christians, and Jews, though class and education mattered more than religion. Three issues galvanised associationalism, writes Juan Cole in his Colonialism and Revolution in the Middle East (1993): European control, viceregal absolutism, and overtaxation and oppression of ordinary people.

Take the Helwan Society, for example, a group of elite politicians who came together in 1879 in the wake of the state’s declaration of insolvency. The Society opposed Dual Control (British and French supervision of the expenditure of Egyptian revenues) and distributed 6,000 copies of their anti-foreign, constitutionalist manifesto. The society took its name from the sleepy retreat where its members were kept under strict government surveillance. The zeitgeist climaxed in the Urabi movement against British control, but it could not survive in the face of British force majeure. The British invaded in September 1882; their last troops left in December 1956.

Between 1882 and the next iteration of mass upheaval in the spring of 1919, association-building was the order of the day. Egypt’s first political parties mushroomed in 1907, and its first professional union saw the light in 1912. Egypt’s venerable bar association was chartered by the state to co-opt leaders of an increasingly central profession, but the association’s lore says it came into being as a response to lawyers’ outrage at the ransacking of a Tanta lawyer’s office by police. The apocryphal story is probably an added accretion reflecting decades of subsequent adversarial relations between lawyers and the state, a tussle that culminated in the massive 1994 lawyers’ protest against the death in police custody of lawyer Abdel Harith Madani.

One of the most remarkable features of ’19 was the mobilisation of peasants. Witness this spirited telegram from residents of Daqahliyya on 23 March 1919: “The Egyptian “fellah” (farmer) has been charged as being ignorant of the rights of his country, but to-day we take part in the demonstration with our Egyptian brethren for the liberty and independence of Egypt. With one heart and tongue we are ready to participate in liberating Egypt and to confront every one who disapproves of this right. We vigorously protest against the internment of Egyptian statesmen and the shooting our liberals with rifles. We hope that these feelings will be confirmed and transmitted to the Peace Conference, in order that it may prevent our blood from being shed, which we never forget until we secure our demands.” What a delicious slap in the face of the NDP’s “New Thinkers”, methinks.

The roiling 1940s witnessed a spurt of organisation-building, as eight new professional unions saw the light, right on the heels of the Judges Club in 1939: journalists in 1941, engineers in 1946, and then in 1949: doctors, dentists, veterinarians, pharmacists, agriculturalists, and teachers’ unions. This decade was also the moment when the committee (al-lajna) took center stage as an innovative organisational tool of political protest, building on a practice pioneered in ’19. When political parties, unions, and professional syndicates proved too restrictive or exclusive to carry forward pressing socio-political demands, citizens from diverse social sites banded together in the form of the public committee, such as the high-profile 1946 students and workers committee. Recall the opening scene of Henri Barakat’s film Fi Baytena Rajul (A Man in our House), a powerful depiction of the massacre of committee students and workers on the Abbas Bridge, orchestrated by a demonic chief of police played by the masterful Tawfiq al-Diqqin.

An important aside: the committee is the parent of the even more ephemeral, loosely-structured cross-partisan alliance. Both have resurfaced in the 1990s-era Palestine solidarity committees, out of which morphed Kifaya. I reviewed this process here.

Egypt’s three presidents have alternately sought to constrain and co-opt both the leaders and rank and file of socially influential interest groups, with varying degrees of success. Let’s review the record. Gamal Abdel Nasser inherited a remarkably organised, institutionally dense society, which he proceeded to demobilise and contain through a carefully orchestrated regime of legal repression, co-optation, and reorganisation of the structures of interest representation. In 1953, he outlawed political parties, a move from which they have never recovered. Contemporary Egypt’s highly contrived, distorted political party life is the relic of Nasser and later Sadat’s planned demobilisation. After the March 1954 crisis, Nasser punished all those social organisations who sided with Muhammad Naguib, principally the legal community. He passed laws intervening in their affairs, packing their general assemblies with public sector lawyers, and curtailing the right to litigation, thus immunizing entire categories of administrative action from judicial oversight, in the process trimming the purview of the judiciary.

In 1960, he nationalised the press, to the unexpectedly enthusiastic response of many journalists, as reported by Salah Eissa. In 1961, he brought the historically independent ulama of al-Azhar firmly under state control, the same year that he nationalised the remaining private vestiges of the economy. But because of his political acumen, charisma, legitimacy, and command of valuable state resources, Nasser was able to manage this taming game with few regime blunders. He was also able to see through a maximum disarming of the opposition. I’ve always enjoyed this description, from the New York Times’ correspondent Jay Walz, writing of the preparatory committee debates of December 1961:

Television viewers have enjoyed the sight of the President matching wits and ideas with some of the country’s best brains—university professors, writers and lawyers, including not a few articulate women.

These “working sessions,” on view every night from 6 o’clock to 9, have given Egyptians their first experience with a spectacle to be compared with a Congressional hearing in the United States.

No one is necessarily on the spot. But it has been fascinating to watch Mr. Nasser, seated at a table before the assembly, listening to the theorists and academicians and exhorting them to come up with practical solutions for Egypt’s vast social problems.

At the working day’s end, Cairo residents crowd the tea shops, chairs and tables spilling right out into the street, to watch the broadcasts. The sessions have had a maximum popular audience, such as the infrequent telecasts of the old National Union Assembly meetings never enjoyed.

The President listens intently and takes copious notes when others speak. Frequently he smiles when someone ventures the opinion that certain solutions offered by the Nasser regime in nearly ten years of revolutionary government have been inadequate.

Once, Khaled Mohammed Khaled, a prominent Cairo writer and journalist, declared that the first thing that should be done was to “give back to the people, even the reactionaries, all their freedoms.” Mr. Nasser arose to defend the right of anyone to differ.

But affability and intelligence were not enough to see Nasser through the most challenging crisis of his rule, the 1967 war. In February-March 1968, a year after they spontaneously poured out onto the streets demanding that Nasser stay in power, Egyptians rose up to demand their pilfered rights, despite their bruised organisational structures. Nasser’s concession of the 30 March 1968 Program promising a return to pluralism and the rule of law was the concrete outcome of the popular intifada, led by students, workers, lawyers, and judges. Sadat’s commissioning of a new constitution was his concession to the pent-up pro-democracy demands.

Sadat’s sparring with organised unions and syndicates was much more adversarial than Nasser’s. Possessing none of his predecessor’s charisma, legitimacy, nor resources, Sadat soon found himself encircled by the very institutions he had himself unleashed, and street protest returned to Egypt with an intensity unseen since the 1940s. Three days after the January 1977 “bread riots”, the New York Times of 21 January reported:

The rioters’ wrath was clearly directed at least in part against President Anwar el-Sadat and his closest associates. A mob surged up to his villa in Giza, a residential quarter of Cairo, and threw rocks. The home of Vice President Husni Moubarak in Alexandria was sacked, according to reports from that city.

Lying on a pile of broken glass was a picture of President Sadat, its frame and cover smashed and with crossed lines slashed across it.

Student demonstrators carried Mr. Nasser’s picture and chanted his name and shouted derisive slogans against Mr. Sadat.

With Sadat’s signing of the 1978 Camp David Accords, a moment untold numbers of Egyptians remember with bitterness and dismay, opposition to Sadat fanned from the streets to campuses to the professional unions. Sadat decreed the notorious 1979 campus statute interfering in student union elections and freezing other campus activities, still in effect to this day. The bar association in particular became the unofficial headquarters of all-purpose dissent, with frequent gatherings denouncing the president. Months before his assassination in 1981, an enraged Sadat unilaterally dissolved the board of the bar association, “the first time a president actually issued a law to dissolve the board!” marveled the late Dr. Muhammad Asfour in his cavernous office one evening a few years ago, his body tensing up as if he was describing events that had happened moments ago, his trademark dark glasses sliding ever so slightly down his nose.

I never had a chance to see Dr. Asfour again to hear him retell his poignant days of activism in the bar. He died in 2002, leaving behind a remarkable legacy of legal activism. He was an uninterruptedly, unequivocally liberal lawyer at a time when it was truly dangerous to be so. And like Mumtaz Nassar, he took his opposition straight to the top, not waiting for a president’s death to criticize him in unadorned, straightforward terms.

Mubarak felt under siege, his regime physically threatened by radical Islamists and morally upstaged by moderate Islamists, especially the latter’s superior relief efforts during the earthquake and effective campaigning in the professional unions. His response was simple: churning out laws codifying state intervention in every social organisation while also aggressively policing all potential sites of mobilisation. Legal and physical repression went hand in hand. The government’s legal tailors set to work: in 1992, Military Decree 4/1992 banned any group from receiving donations without prior government permission. In the same year, a new “anti-terrorism” law was passed toughening sentences for criminal offences and extending the jurisdiction of the State Security Courts.

In 1993, the Orwellian-named “Law for the Guarantees of Democracy in Professional Associations” stipulated disabling quorums for elections and paved the way for the freezing of all influential professional unions and placing them under government receivership (with the exception of the journalists’ union).

In 1994, overturning decades of customary practice, legislation was passed requiring village chiefs and university deans to be appointed by the administration rather than elected by voters and professors. Faculty say universities have been turned into adjuncts of the Interior Ministry, with hiring, promotions, and research all subject to the writ of security forces. Scores of academics have also been enlisted in Gamal Mubarak’s Secretariat for Policies (see their names here).

In 1995, a new law was issued toughening penalties for libel to up to five years’ imprisonment in addition to a hefty fine. Mobilisation by journalists succeeded in reducing the fine and the sentence to a maximum of two years, but Mubarak’s 2004 promise to do away with imprisonment altogether remains unfulfilled.

In 1997, the new rural tenancy law rolling back Nasser-era gains for peasants took effect, spurring violent disturbances in the countryside and the eviction of peasants off the land by landlords in collusion with police forces. The March events in Sarando are a direct echo of this process.

In 1999, the government rammed through parliament law 153/1999 severely restricting and monitoring the activities of NGOs. Though a Supreme Court ruling declared the law unconstitutional in 2000, the government was undeterred; it rebounded with law 84/2002, which by all accounts is even worse than law 32/1964 which it replaced.

In case this intricate web of laws is not enough, there’s always the trusty “Emergency Law” (162/1958), applied uninterruptedly since 4 pm, 6 October, 1981. In its bare bones essentials, it enables the state to do anything, literally anything, in the event of a national emergency, defined by the regime as the threat of terrorism and narcotics trafficking. The street demo slogan captures it best: “Ya huriyya feinik feinik, al-taware’ beini w’beinik!” (Freedom freedom where are you? Emergency stands between me and you!)

With a tailor-made restrictive law for every social group, at least a decade of intense security forces’ interference, the ubiquity of the police state woven into the fabric of daily life, and the near-complete withdrawal of the government from any service provision, the state has become all stick, no carrot. Remarkably, during Mubarak’s presidency, the state has managed to systematically alienate every organised social group and every unincorporated sector (the urban poor and landless peasants) save its own very narrow social basis of crony businessmen and the army.

Egyptian society is an interlocking patchwork of sturdy associations, but during the past 15 years these organisations have been subject to aggressive state control in the form of repressive laws and direct government interference. Such are the conditions spurring the currently snowballing democracy drive. Combined with tough economic conditions, a threadbare social safety net, and American pressure on the regime (albeit inconsistent and ambiguous), it’s difficult to see how the status quo is sustainable.

When regime hacks claim that Egyptians aren’t ready for democracy, or when foreign know-nothings pontificate about the baby steps of democracy, or when Egyptians entrenched in the status quo wrap their fear of change in claims of the unsuitability of democracy, I can only marvel at the brazen spinning of such rank lies.

And then I reach for my nearest history text. There I don’t find comforting proof of Egyptians’ readiness for democracy, for that is not and never has been the issue. Nor do I find triumphal stories of democratic happy endings, for that is not how democracy comes about. I do find a dizzying diversity of socio-political mobilisation, a fevered clash of interests, heated contests of ideas, high-stakes political brinksmanship, stupendous miscalculations, felicitous and unexpected advances, regrettable losses, shameful failures, and everything in between. In sum, a chequered political history of one democratic step forward, three steps back. The puzzle is not that we have not yet achieved democracy, but that there are those who would rob us of this history, distort and falsify it, and package it into a claim that Egyptians lack the maturity “necessary” for democracy.

I’ve made clear where I think such claims belong. Let me make one more thing clear. The behavior of the Egyptian political establishment, the regime with all its agencies and factions, the first family with all its individuals, the NDP with all its hangers-on and apologists: all evince an alarming lack of coherence, forget ingenuity. Utterly bereft of any legitimacy, competence, popularity, or mandate, is it any wonder that they’re resorting to legal subterfuge, paid mobs, physical assault, and rotten theories?

Wednesday, May 25, 2005

Referendum on Article 76

Rented Mubarak demonstrators corner a Kifaya member as a colleague pulls him to safety, 25 May 2005.

“I have boundless confidence in your participation in the referendum, to make a new tomorrow for our homeland, achieve new horizons for our political life, and take confident steps to a better future.” Hosni Mubarak, al-Ahram, 25 May 2005.

Mubarak demonstrators burn a Kifaya banner.

“I would say that President Mubarak has taken a very bold step. He's taking the first step to open up the elections, and I think that's very, very important. As you know, every -- you have to be slow as you do each of these steps.” American First Lady Laura Bush, 23 May 2005.

All photos from the Associated Press.

Two days after Laura Bush and Suzanne Mubarak held their summit meeting about the necessity of girls' and women's “empowerment” in the Middle East, Mubarak's hired thugs battered and sexually assaulted women protestors and reporters, as they did during the 2003 anti-war protests and during parliamentary elections. AP reporter Sarah al-Deeb is no stranger to Mubarak's thuggery, this is the umpteenth time she gets assaulted while doing her job. Women were pulled by the hair, punched and kicked, and dragged on the ground until their clothes came off, while policemen stood by watching. To all the women and men who had their bodies violated while peacefully demanding self-rule today: your pains are not forgotten, your bravery humbles us, your souls edify us. Your blood is on the hands of this despotic regime, until and beyond the day of reckoning.

Monday, May 23, 2005

The Vexed Issue of International Election Monitoring

Judges' Club President Zakariya Abdel Aziz outlining Egyptian judges' conditions for supervising the fall elections. 13 May 2005.

No doubt this will be one of the most contentious issues this election year, with everybody who’s anybody weighing in on the matter. The American government has made its position clear: it wants international monitors. Never mind that the Bush administration has zero credibility to demand anything, least of all election monitors. The travesty of polling in Florida during November 2000 springs to mind, leading to international election monitors for the 2004 American poll. But worry not, the cornered Mubarak regime dares not bring up any of this, it’s too busy sending its hapless envoy to Washington and NY to grovel and remonstrate with its increasingly impatient patron. For about 10 minutes, I actually felt sorry for Ahmed Nazif.

The man got a good drubbing everywhere he went on his fool’s errand. But then he lost my pity when he started whining like a loser and spewing inept stupidities lifted straight out of Gamal Mubarak’s phrase book. Skeptics should give Hosni Mubarak’s reform antics “the benefit of the doubt”; “Is it really forbidden for a son of a President to be active politically? You should focus on the process, not on the people,” and “Egyptians are very kind people by nature. And kind people are easy to influence.” Finally, the kicker, on why Egyptians aren’t yet ready for democracy: “There is a maturity process that has to take place.” Dear Mr. Nazif, pardon my immaturity, but please shut up and go back to devising “e-government” initiatives or whatever it is you were originally hired to do. Stop making an utter fool of yourself by pontificating on that which you do not comprehend. It’s irritating.

While Nazif hemmed and hawed in the U.S. over international monitors, offering up his unsolicited and irrelevant “personal opinions,” his boss was all chest-thumping and indignation about the issue. Gamal Mubarak vowed ungrammatically (but details details): “Egypt will not be imposed any model of control from outside.” Now, as impressed as I am that Mr. Globalization really is a jealous nationalist at heart, I have one niggling question: is it part of democracy that someone who holds no cabinet post nor has ever been subjected to any mechanism of accountability parade around disbursing authoritative public statements? I’m just wondering. Of course, it could just be that Gamal Mubarak is privy to a state of the art theory of democracy of which I’m not aware. He’s been awfully active of late, lecturing opposition parties on what they need to do to avail themselves of the unprecedented democratic opportunities conceded by his father. I refer you to the daily al-Ahram of the past few days, which has been a faithful transcriber of Gamal’s every precious nugget of fraternal advice.

The American Connection

Among thinking commentators, the issue of international involvement in Egypt’s upcoming elections has sparked serious debate. Ex-judge Tareq al-Bishri wrote an important article in al-Araby coming down against the idea, while al-Ahram Weekly surveys favorable opinions among other thinking intellectuals. Let’s remind ourselves of some important facts: election monitoring has always been a very sore point for the regime, and it’s been up to domestic monitors to confront it on this politically taboo topic. Recall the 1995 parliamentary elections, the bloodiest in Egypt’s history (60 dead and hundreds wounded). The Egyptian Organisation for Human Rights and sister groups were valiant, unheralded monitors, documenting all manner of NDP abuses, including the ruling party's fomenting of the ugliest form of sectarian bigotry in its campaigning, specifically in the district of al-Daher (see the EOHR’s Report Nobody Passed the Elections for this and other lurid details). When sociologist Saadeddin Ibrahim said that his Ibn Khaldoun Center would monitor the 2000 poll, he was swiftly charged with “tarnishing Egypt’s image” and summarily dispatched to the first of his two trials. If my memory serves me correctly, not a word was heard back then from the American government and its Middle East democracy engineers about the necessity of election monitoring. Back then, you see, the American administration was perfectly happy with the adequate services of the Mubarak regime. It saw no reason to rock a perfectly steady boat.

These are different times, however, and the U.S. administration and its army of instant Middle East democracy experts and their “Middle East Partnership Initiative” are now very very concerned about free and fair elections in Egypt. Yes, very very concerned, and so they want to see Egypt become a shining beacon of democracy to its neighbors, and they don’t buy Mubarak’s pathetic scare tactics anymore about the Islamists taking over. The Americans are fed up with the crusty Mubarak regime, it seems, and have settled on free elections as the legitimate and smart way to ease said regime out of power. The road to the Americans’ new plans for the Middle East runs through reasonably competitive elections, with international monitors. Hence all the stern warnings to Mubarak over Ayman Nour (the Americans’ new favorite after they dumped Gamal Mubarak), the cancellation of Condoleezza Rice’s Cairo trip, her friendly signals to the Islamists, and above all, the Americans’ sudden concern for what the Egyptian people want. Listen to Richard Boucher, American State Department spokesman, as he mulls over Mubarak’s reform: “Is it enough progress? Is it going to do what the Egyptians and we and, more important, people in Egypt want?” he asked. “We’ll see.” With so much pressure at home and abroad, is it any wonder that Gamal Mubarak has been looking so haggard lately? Looks to me like he’s not getting enough sleep. Tsk tsk.

Delicate Domestic Processes

The American administration’s utterly self-interested concern for international monitors is likely to considerably complicate the debate in Egyptian circles. The Egyptian government will cry “national sovereignty”, decry foreign meddling, and quietly try to woo back the Bush administration, all at the same time. Most damaging, it will also play on Egyptian judges’ turf instincts and sell international monitors as an attempt to impugn the reputation of the Egyptian judiciary. As we know, judges are embroiled in their own serious battle with the executive to meaningfully supervise the elections. Judges are not going to take kindly to upstart international monitors parachuting in to step all over their turf. The executive can use the cudgel of international monitors to break the judges’ unified ranks and compel them to submit to election monitoring shorn of their clearly stipulated conditions of 13 May. This is why many Egyptians, myself included, would be perfectly happy with judicial monitoring on the judges’ terms, sans international observers. And given the significant pre-election maneuvering at which the government is so adept, particularly drawing up voter rolls to include hundreds of ghost voters and dead people, I really don’t see how any team of international observers can get at some of the most pernicious forms of fraud and rigging.

International election monitoring is an excellent idea, but not for the 2005 Egyptian poll. In my opinion, it’s a great idea that comes at a very bad time, not because the Egyptians are not ready or any such insulting nonsense, and not because of faux nationalistic drivel, but because of the high probability that it will torpedo a much too precious and delicate ongoing process. The judges’ struggle is too important to be sabotaged by an issue the Americans are pushing cynically and the Egyptian government is all too willing to deploy craftily. Much more effective would be domestic monitoring by Egyptian human rights groups, with moral support from the internationals, and both supporting and aiding the judges, not supplanting them. Only then will judges gain the control and prerogatives they’ve been seeking, and perhaps even invite international observers of their own accord. But until then, thanks but not this year.

An Inspirational Model

In the long run for Egypt, I can think of no better system than India’s venerable and exemplary Election Commission, a pillar of the Indian political system that has been ably and effectively administering elections since 1950. An autonomous, constitutional body, the Commission administers elections from A to Z, enjoys an independent budget, and its decisions can be challenged before the courts. “It is the Commission, which decides on the location of polling stations, assignment of voters to the polling stations, location of counting centres, arrangements to be made in and around polling stations and counting centres, and all allied matters.” Election Commissioners “enjoy the same status and receive salary and perks as available to Judges of the Supreme Court of India. The Chief Election Commissioner can be removed from office only through impeachment by Parliament.” The Commission’s renown is such that its members often serve as international election observers.

An independent commission is the only way Egyptian elections can be safely conducted, far from the stranglehold of the executive branch. It has the potential to remedy all the ills plaguing our elections since the 1940s, and would fit in perfectly alongside Egypt’s robust judiciary and its hard won powers of judicial review. The idea is already gaining ground among Egyptian legal experts, who no longer deem it sufficient that elections be conducted under the aegis of the Justice Ministry (to say nothing of the current travesty of the Interior Ministry coordinating elections). Above all, an independent Election Commission would restore confidence in the game of elections and reinvigorate and rationalise the entire political process in Egypt. It addresses Bishri’s fears of foreign-inspired fragmentation and leaves room for international observers to come in from positions of parity, not imperious inspection more interested in discrediting a regime on its tottering last legs than empowering the average Egyptian voter.

Wednesday, May 18, 2005

To be Poor in Egypt

Mahmoud Said's "Bakus Cemetery in Alexandria's Raml" (1927)

Apropos of this bankrupt regime’s criminal and disgusting use of poor Egyptians to assemble and yell pro-Mubarak chants:

al-Araby’s inimitable Gamal Fahmy has a heartbreaking rumination on these folk this week, ending his column with a tragic, painful image only a sentient writer of his sagacity can observe and retell.

I don’t doubt that many others were pained and outraged last week by the busing in of poor Egyptians to shout stock slogans against Kifaya and “for” Hosni Mubarak: “Ya Mubarak doos doos, ehna ma’ak min gheir fuloos!” (Oh Mubarak step on them step on them, we’re with you without any money!) Gynecologist and Gamal Mubarak crony Hossam Badrawi reportedly dispatched his henchmen to collect idling men at ahwas and poor women from shantytowns and deposit them across the latest Kifaya demonstration. They lure them with a promise of a fuul sandwich and £E20 that whittles down to £E16 after the go-between takes his cut (read Gamal Fahmy on this poignant detail).

Cairo’s poor take center stage only when there’s an armed attack or the regime needs last minute constituents to parade in front of the world. Then they’re pulled out of their lairs of invisibility and dragged in front of the cameras for “social experts” to dissect. Witness the sick voyeurism with which journalists and “poverty experts” descended on Shubra al-Khayma after the Sayyeda Zeinab and Tahrir bombings, wringing their hands at the poor’s lack of privacy, paved roads, water, education, nutrition, what have you. What colossal levels of willful ignorance, atrocious taste, and abuse leads ostensibly enlightened Egyptians to pretend that they agonise and care about the poor in their hovels? It makes me physically ill to hear respectable “social scientists” pontificate about a culture of poverty and “obscurantist extremism” that feeds conservatism and social violence. Everyone wanted to advance his or her own brilliant theory, everyone scrambled to test the latest “explanations” parroted slavishly from whatever fourth-rate textbook they could get their hands on, everyone competed to violate these people once again in the carnival of commentary that erupted after the bombings.

As for the regime, there is nothing more sickening than Suzanne Mubarak’s “inauguration” of a community center in Ezbet el-Walda in Helwan last week, an event redolent of Marie Antoinette’s games of dress-up and let’s-pretend-to-be-poor. That Empress was at least open about her blithe “let them eat cake” attitude, but Suzanne Mubarak seriously aspires to appropriate the rights of citizenship as a token of her personal benediction. How revolting the sight of the president’s wife surrounded by her servile officials and latest posse of ladies who lunch as they gaze down superciliously at one of the most impoverished corners of Cairo, venal state television cameras there to capture it all and bring us the good tidings on the 6 o’clock news.

How deeply painful the disingenuous, incongruous sight of kindly, modest Egyptian mothers forced to hold aloft posters of Hosni Mubarak and shout ugly, belligerent slogans alien to their sweet natures and reflexive kindness. Just when we think it’s impossible for this regime to stoop lower in its cynical manipulation and abuse of all citizens, but especially the poor, it reveals a diabolical knack for grabbing at anything to ensure its own miserable survival. Most tragic of all is the double exploitation of Egypt’s poor: those garbed in black and armed with truncheons encircling those dressed in rags and armed with “Yes to Mubarak” posters and cheap drums. The wretched stand shoulder to shoulder with the duped, separated by years of fear, pauperisation, and the systematic theft of their basic human dignity.

But Hosni Mubarak says, “Don’t ever believe that anyone goes to bed without supper in Egypt, with the difference being that one person eats meat and another eats fuul. Personally I like to eat a fuul sandwich. Egypt is the land of peace and prosperity and no one goes hungry here.”

To erase from my mind the false sight of poor Egyptian women carrying Mubarak posters or forced to pay deference to his wife, I think of them as I see them: at the mouth of Sharia Qasr al-Aini selling tissues and plastic combs; in Midan al-Gami’ chopping carrots and shelling peas to sell to pampered housewives; in the Metro selling trinkets and hairpins; in the markets hawking gebna arish and legumes; outside the Sa’d Zaghlul Metro station good-naturedly haggling with homebound government clerks over bunches of sun-wilted dill and knobby potatoes; in the miserable latrine of Alexandria’s Mahattet Masr train station, permanently hunched over to wipe the floor with an ancient, drenched rag; outside Metro Market offering up clumps of baladi mint and juicy lemons; at the corner of Sharia al-Kneesa in Alexandria selling newspapers and magazines; wandering the draughty corridors of Detainees’ Affairs in the courthouse on Sharia al-Gala’, seeking the whereabouts of their imprisoned sons; clutching their babies as they try to cross the deadly Autostrade near Manshiyyet Nasser; making the long trek from al-Marg and el-Gabal el-Asfar to clean the homes of the upwardly mobile; and stealing a few moments in the refuge of al-Azhar, quietly murmuring words of supplication before walking back out into a chaotic world indifferent to their sufferings. Listen closely to their anodyne prayers, before they waft up to the ears of angels.

Saturday, May 14, 2005

The Judges Speak

Cairo Court of First Instance, 31 December 1933.

In a landmark hours-long meeting on Friday, 13 May, around 3,000 Egyptian judges issued a resounding ultimatum to the executive. If they are not granted complete supervision over elections from A to Z, and a new law guaranteeing full judicial autonomy, judges will withdraw from supervising both the September presidential vote and the November parliamentary poll, refusing to be "false witnesses". Braving tremendous government inducements, oblique threats, and serious skepticism within their own ranks, the extraordinary General Assembly of the Judges Club in Cairo (Nadi al-Quda) echoed the position of the Alexandria judges statement on April 15 threatening to boycott elections if they are robbed of meaningful supervision. The regime has until September to meet the judges’ demands. The battle for democracy has spread within the state, as Egyptian judges reclaim a proud tradition of corporate solidarity and public activism against their longstanding nemesis, the almighty executive.

Update: In a swift counter-attack, The Supreme Judicial Council (Magles al-Qada' al-'Ala) has issued a statement published in Tuesday's al-Ahram (17 May) asserting its sole right to represent judges and claiming that election monitoring is judges' "sacred duty" subject to no conditions. Note that reforming this organ is one of the longstanding demands of the judges, who oppose the president's power to appoint its sitting magistrates. The statement is a fierce attack on the judges' landmark meeting, claiming that the thousands who showed up friday (estimates range from 3,000-5,000) constitute "a minority that does not represent judges." In a dangerous move designed to sideline the intrepid, autonomous, and historic role of the Judges Club, the statement threatens, "The Supreme Judicial Council has decided not to recognise any opinion imputed to judges unless it emanates from the general assemblies of courts or is affixed with their signatures." The problem of course is that such general assemblies are thoroughly controlled by the Ministry of Justice. So let the battles begin. Judges are fed up and outraged enough not to back down. They see this as their last stand for their own professional integrity, and Egyptian citizens will watch with baited breath as the last of the honorable men stand up for our rights. Read the great Mahmoud al-Khodeiri's statement to the friday meeting. "The time has come to end tutelage," he said. Call it the battle cry of the Egyptian people's spring, 2005.

I never anticipated that Friday’s General Assembly would follow through on the actions of the Alexandria faction. Between April 15 and May 13, the executive has been doing its damnedest to persuade the judges to cease and desist. Justice Minister Mahmoud Abu el-Leil (former Giza governor) has been lobbying intensively in the provinces, dangling lucrative carrots and quiet sticks before judges to keep them in the election game. He promised pliant judges an increase in their bonus from £E6,000 to £E12,000, and the heads of the Tanta, Bani Sueif, and Qalyoubiyya judges clubs have caved (though not the general assemblies of these clubs). The credibly clued-in Abdalla al-Sennawi reports that presidential goodwill ambassador Makram Mohamed Ahmad was dispatched to Alexandria to convince judges to go easy on the regime in the parliamentary elections, at which point the intrepid Alexandria Judges Club president Mahmoud al-Khodeiri abruptly ended the meeting.

Three months ago, no one outside Egypt gave a hoot about Egyptian judges, except of course those cloying do-gooders at USAID with their judicial “training” or whatever they call them programs to improve the natives. Now the foreign media has discovered that Egypt has judges, and—gasp!—they’re demanding reform. I won’t be surprised if the American administration and its house intellectuals start to take credit for the judges’ moves, while the Egyptian administration and its scribblers heap calumny on any groups demanding democracy (look no further than Hosni Mubarak’s comical utterances to that purveyor of cutting-edge journalism, the Kuwaiti al-Seyassah). But because there’s nothing uglier than falsifying history for base political ends, let this be a corrective.

There’s no denying that the general democracy zeitgeist offers a valuable opportunity for judges to stake their claims. But the real reasons we’re seeing judges stand up and deliver today are rooted in Egyptian domestic politics and Egyptian history. This election year, judges are determined not to repeat the travesty of the fall 2000 elections, when they were trapped inside polling stations as government thugs blocked off roads, turned back voters, and bussed in government supporters to make sure the NDP dominates parliament. This rude awakening dovetailed with longstanding tensions between the executive and the judiciary over who controls judicial appointments, salaries, bonuses, and discipline, and the very integrity of the judicial profession. It’s an open secret in Egypt that police officers can easily become judges by taking an accelerated (and predictably bogus) one-year diploma in law. Add to this the increasingly brazen use of fake judicial implements by the Mubarak regime to evade upstanding judges (State Security courts and military tribunals to name just two). Wrap it all up with a high degree of corporate solidarity among Egyptian judges, borne out of previous struggles with the state, etched in a vibrant collective memory and a rich judicial lore. What you get is something like John Locke’s revolutionary situation: “Great mistakes in the ruling part, many wrong and inconvenient Laws, and all the slips of humane frailty will be born by the People, without mutiny or murmur. But if a long train of Abuses, Prevarications, and Artifices, all tending the same way, make the design visible to the People, and they cannot but feel, what they lie under, and see, whither they are going; 'tis not to be wonder'd, that they should then rouze themselves, and endeavour to put the rule into such hands, which may secure to them the ends for which Government was at first erected…”

Just two years after the Court of Cassation (Mahkamat al-Naqd) was established in 1931 as the nation’s highest appeals court, it carved for itself a reputation as a defender of citizens’ rights against a pernicious Egyptian tradition: state torture. On 19 March 1932 in the Asyut village of Badari, the district police chief was shot. The two young assailants were tried, convicted of premeditated murder, and one was sentenced to life with hard labor while the other was meted the death penalty. Against all odds, valiant defense attorneys and prominent lawyers Morqos Fahmi and Ibrahim Mumtaz appealed. In 1933, the Court of Cassation, headed by Abdel Aziz Fahmi (one of the companions of Saad Zaghlul in the November 1918 delegation to Sir Reginald Wingate demanding Egyptian independence), overturned the lower criminal court verdict. The Court surmised that the crucial condition of premeditation was absent, due to one of the assailant’s previous and humiliating torture at the hands of the murdered police chief. The emasculating mechanisms of torture in the 1930s could be lifted straight from the gruesome tales we hear today of police stations turned into torture chambers. In one of those endlessly fascinating historical twists, defense lawyers’ major witness was Mohamed Nassar, mayor of Badari, and father of future judicial luminary Mumtaz Nassar.

Judges conferred and socialized with one another in the deceptively patrician-sounding Judges Club, established in 1939 “to strengthen the bond of fraternity and solidarity among all judges, to care for their interests, and to facilitate their meetings,” as its founding charter stated. An explicit goal of the Club was to raise funds to help judges with cost of living issues so that they need not turn to the government and offer it avenues of influence. The government of course deemed the Club too dangerous to let alone, and insisted on having it be monitored and accredited by the Ministry of Social Affairs, a condition that judges have long chafed under and have since been endeavoring to overturn.

That 1954 incident is remembered as the “sinful attack” (al-i’tidaa’ al-athem) in judicial lore, and constitutes the first salvo in judges’ quiet war to regain their autonomy from a hungry executive. Between 1954 and 1969, the Nasser regime engaged in a bitter struggle to rein in Egyptian courts and their wildcard overseers, using a clever menu of manipulation and machination designed by wily legal tailors (many of them former judges drafted into the executive). The next incident came in 1968, when judges joined students and workers in expressing their outrage at the lack of democracy and attendant military defeat at the hands of Israel. In another landmark Judges Club meeting, on March 28, 1968, steered by president Mumtaz Nassar and vice president Yahya al-Refai, Egyptian judges unanimously agreed to issue a statement that has since assumed an exalted place in the pantheon of pro-democracy ephemera in Egyptian history. As Nassar proudly reminisces in his memoirs, the statement received a 15-minute standing ovation from the club’s General Assembly. It reads in part, “There is no doubt that the strength of the domestic front requires above all removing all the obstacles placed by pre-1967 conditions in the way of citizens’ freedom…Individual liberty in expression and assembly must be ensured for every citizen, to participate via criticism, dialogue, and proposals, to feel responsible for and capable of free expression. This cannot come to pass without asserting the principle of legality, which means in the first instance providing freedoms to citizens and the rule of law over rulers and ruled alike.”

Interior Minister Sha’rawi Gom’a was livid that the judges spurned his multiple entreaties and pleas to delay the statement, and their earlier stubborn and collective refusal to join the single-party Arab Socialist Union. A secret cabal of judges loyal to the government was deployed to foment dissension among judges and rig the March 1969 Judges Club elections. When Nassar and Refai’s slate won despite the spoilers’ best efforts, it was the last straw. On August 31, 1969, Nasser decreed a quartet of laws under the rubric “Judicial Reorganisation” by which he instantaneously fired and then re-hired the nation’s judges minus 189 who were either transferred to administrative posts or retired early. Nassar and Refai were among the 189. This second episode stands in judges’ collective memory as “Madhbahat al-Qada’” (The Massacre of the Judiciary). Yet there was a fascinating silver lining. One of the four laws specified a new court organ called the Supreme Court (al-Mahkama al-Ulya) designed to centralise and monitor the country’s dispersed judiciary by monopolising judicial review. A retired minister of justice named Badawi Hammouda was reluctantly pulled out of quiet retirement to head the toothless new body, “a political court” as judges derisively panned it at the time. Just ten years later in 1979, they rose to its defense in its new incarnation as the Supreme Constitutional Court, a powerful and central player in the Mubarak years under the presidency of Awad al-Morr.

A tribute to Mumtaz Nassar: the young law student who came of age watching his father testify at the Badari trial and listening to the rousing defense speeches of Fahmi and Mumtaz would become not just a formidable advocate of judicial autonomy, but a thorn in the side of two presidents. Defending the Judges Club against the Nasser regime’s legal henchmen, he went on to become the leader of parliamentary opposition to Anwar Sadat. Nassar prefigured judges’ face-to-face encounter with electoral fraud in 2000, not as an observer but as a candidate. His supporters faced off with police in Assiut in a tense and potentially bloody battle in the 1979 elections; only a personal phone call from Sadat himself ended the standoff, Nassar won by a landslide, and became an opposition legend, following in the footsteps of Mustafa Mare’i and inspiring the likes of Mahmud al-Qadi.

As for Yahya al-Refai, he’s alive, refreshingly outspoken, but sadly less well, though his wry sense of humour is as sharp and cutting as ever. His lawsuit appealing his dismissal was accepted by the Court of Cassation in 1972, and he resumed his judicial career, becoming president of a Cassation Court circuit until his retirement in the 1990s. In 1986, at the first Justice Conference which Mubarak inaugurated, he stunned the audience by setting aside his prepared remarks and calling on the president to lift emergency law, to the judges’ resounding, grateful applause (the president was furious and walked out). Refai then took up the cause of judicial autonomy, embracing the project of a new law governing the judiciary in place of the current law of 1972 vintage. It is his and his colleagues’ draft law that has gathered dust in many a ministry of justice drawer since 1991, to be taken up once again by Alexandria’s and then Cairo’s judges in 2005.

The July 2000 Supreme Constitutional Court ruling requiring judicial supervision of elections, for the first time in Egyptian history, was issued by a slight, dapper man with piercing blue eyes and a strong resemblance to the debonair screen star Ahmad Mazhar. Muhammad Walieddine Galal is a charming, grandfatherly man who loves Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 and spends his retirement days listening to it in a quiet, perfectly appointed, old-fashioned drawing room with curtains drawn against the brutal sun and crocheted doilies on the armrests. His memories as a young legal adviser in Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Bureau Technique (Maktab al-Fanni) are never far from his mind, recalled with startling lucidity, as are his school days in 1940s Heliopolis. What did one do as a legal adviser to Gamal Abdel Nasser? “There was a wonderful balcony where we sunned ourselves in the winter,” he says with an elfin smile.

The case Galal ruled on was filed by lawyer and independent candidate Kamal Hamza al-Nasharti, who argued that police interference hurt his chances in the 1990 elections. Multiple theories abound for why the case took 10 years to make it through the Court’s system (the average time to decide a case is 2-3 years), but when Galal’s ruling came down it sent shockwaves through the political system. From simply reviewing hundreds of appeals of elections results (and issuing only non-binding reports as delimited by Article 93 of the constitution), Egypt’s judges would suddenly have the power to monitor the poll. Judges and independent candidates alike hailed it as a real step for democracy, the unprecedented violence of the 1995 elections fresh in their minds (at least 60 dead and hundreds injured). The ruling party and its henchmen paid lip service to a clean vote while power brokers scrambled behind the scenes to retain their hold amidst the new conditions. Significantly, government legal tailors willfully interpreted the ruling to include government lawyers and prosecution members as part of the “judicial organs” eligible to supervise the vote.

Elections were conducted in three phases to allow the limited number of judges to travel and oversee all polling stations. While there was a very high degree of turnover between the 1995 and 2000 parliament, the 87.7% NDP majority (after the hurried scrambling of nominal independents back into the government fold) was still a disappointment. The regime was able to successfully claim victory on both counts: its international image and domestic standing were temporarily burnished by the participation of judges, and it had a healthy majority, above the minimum 2/3 required to pass important legislation. However, within the ranks of judges, the experience did not palliate but rather inflamed their discontent at executive intervention in budgetary and disciplinary affairs. Skirmishes between judges and policemen at polling stations fed gathering discontent at a litany of issues: from overcrowded courthouses to executive interference in the assignment of cases to the epidemic of appointing judges as highly paid legal consultants to government ministries (setting off a conflict-of-interest morass, especially among administrative court judges adjudicating disputes between citizens and government agencies).

Judicial discontent literally hit the newsstands in early 2003 when some opposition newspapers published Yahya al-Refai’s startling revelations of the Ministry of Justice’s methodical campaign to corrupt and divide judges. As Mubarak played up his appointment of lawyer Tahani al-Gebali to be the first woman judge and designated Coptic Christmas a national holiday, Refai exposed the dark underbelly of executive-judicial relations. The minister appoints justices to courts for as long as he wants and has powers to discipline and transfer judges, said Refai. He touched on the sensitive issue of judges’ income, describing how a freeze on their notoriously meagre salaries was complemented by a system of selective bonuses to identify pliant judges and punish upstanding ones. For the first time since the British occupation in the nineteenth century, Refai continued, the ministry has required judges to provide it with copies of civil and criminal suits against important officials, and adopted other measures to influence the outcome of high-profile cases.

Refai’s allegations emboldened other judges. Tareq al-Bishri penned a study on the various containment and intervention strategies used by successive Egyptian regimes to subordinate and curtail judges. Judges Club board member Ahmed Saber wrote a detailed, first-hand account of the rigging and intimidation he observed in the 2000 vote and published it in the Judges Club journal. Issues of judicial autonomy, self-governance, and supervision of elections were smoothly twined as judges in the provinces shared their horror stories of understaffing and overwork with judges in the big cities. Older judges sensed a palpable decline in the quality and training of new judges, particularly those entering the profession through the police academy route. In many ways, judges experienced the same pressures as other professionals: declining resources, autonomy, and pay combined with increasing caseloads, undue intervention by the government, and shocking tales of institutionalised corruption in what is widely perceived as the last institution to hold any semblance of public confidence.

Two radicalising events came in March 2004, when a thoroughly tamed Supreme Constitutional Court under the presidency of a compliant judge issued a binding interpretation of the contested “judicial organ” definition in Article 88 of the Constitution concerning who gets defined as a judge, to supervise elections. Flying in the face of a widespread consensus in the legal community that a judicial organ must be defined narrowly as a court adjudicating cases, the Constitutional Court adopted the looser definition of the term to include government lawyers and prosecutors whose loyalty to the government is part of their job description, and thus whose competence to impartially oversee elections is doubtful. Then on March 12, 3,000 judges gathered at the Judges Club for another extraordinary General Assembly to protest warnings issued by the Supreme Judicial Council against judges Hossam al-Ghiryani (see more on him here) and Ahmed Mekki, two Alexandria judges who spearheaded the boycott idea last month.

Days of Action

Egyptian judges’ action this year is thus built on real grievances festering for at least a decade, declining morale and professionalism due to aggressive executive interference, and powerful collective memories forged out of past struggles and the examples set by revered figures. But we have seen this type of activism before, at least as far back as 1968. At the same time, there is something significantly new. The executive desperately needs judges to certify the regime’s elections, most especially during this annus horribilis of intense international (read American) scrutiny of the Mubarak regime. Savor the irony: while for years the regime resisted and battled judicial supervision, it now craves it as legitimising cover after being compelled to accept it by Galal et al’s July 2000 ruling.