Mr Anwar Sadat had a notorious but particularly apt expression whenever he embarked on one of his endless authoritarian manoeuvres. “It’s all by law!” (kullu bil qanun!) he would intone. Indeed, Egypt’s rulers have always understood that violent repression alone is never enough to control a complex society of guilds. So they have found in rule by law an utterly indispensable tool to certify and smooth the project of social control. Gamal Abdel Nasser understood this, and so does Sadat’s less colourful though no less devious successor.

Mr Anwar Sadat had a notorious but particularly apt expression whenever he embarked on one of his endless authoritarian manoeuvres. “It’s all by law!” (kullu bil qanun!) he would intone. Indeed, Egypt’s rulers have always understood that violent repression alone is never enough to control a complex society of guilds. So they have found in rule by law an utterly indispensable tool to certify and smooth the project of social control. Gamal Abdel Nasser understood this, and so does Sadat’s less colourful though no less devious successor.From day one of his tenure, Mubarak invoked the handy legal tools bequeathed to him by his predecessors. But given how systematically and uninterruptedly he has been pilloried for the past three years, it was only a matter of time before his regime resorted to obscure legal provisions that had long fallen into disuse. And so the improbable subject of law has permeated nearly every political struggle of the past few years.

If we focus on just the past six months, there’s the judges’ saga and its many intricate details. And the farrago of charges brought against demonstrators assaulted and detained for peacefully expressing their solidarity with judges. And the criminal case against journalist Wael al-Ibrashi et al for publishing the “black list” of judges alleged to have participated in election fraud. And the lower court ruling against al-Dustour editor Ibrahim Eissa and journalist Sahar Zaki for simply reporting on a routine suit. And the current battle over new legislation governing “press offences.” There’s no single thread connecting all of these events, except that they all dramatise the modern political struggle between a repressive state wielding draconian laws, and citizens seeking the repeal and reform of such oppressive ordinances.

A Cornucopia of Crimes

As with any authoritarian state worth its salt, the Egyptian version has stacks upon stacks of repetitive, overlapping, ambiguously worded laws designed to control and constrain every aspect of life. Let’s take the notorious Assembly Law 10/1914 (right), crafted immediately after the outbreak of WW I. Still very much in use, provisions of this law are repeatedly invoked against peaceful demonstrators, most recently those detained in April and May for expressing their solidarity with judges. Articles 1 and 2 criminalise any gathering of at least five people that “endangers public peace,” “obstructs the implementation of laws and statutes,” or “influences authorities carrying out their duties.” The punishment is imprisonment for no more than six months or a fine that does not exceed £E20 (if weapons are involved, the punishment is increased to two years or £E50).

As with any authoritarian state worth its salt, the Egyptian version has stacks upon stacks of repetitive, overlapping, ambiguously worded laws designed to control and constrain every aspect of life. Let’s take the notorious Assembly Law 10/1914 (right), crafted immediately after the outbreak of WW I. Still very much in use, provisions of this law are repeatedly invoked against peaceful demonstrators, most recently those detained in April and May for expressing their solidarity with judges. Articles 1 and 2 criminalise any gathering of at least five people that “endangers public peace,” “obstructs the implementation of laws and statutes,” or “influences authorities carrying out their duties.” The punishment is imprisonment for no more than six months or a fine that does not exceed £E20 (if weapons are involved, the punishment is increased to two years or £E50).In addition to crimes scattered throughout individual ordinances and those compiled in the Code of Criminal Procedure (Qanun al-Ijra’at al-Jina’iyya), the magnum opus of Egyptian crime is of course the trusty Penal Code, Qanun al-‘Uqubat, promulgated on 31 July, 1937 (the image at top is a copy of its antique 1904 forbear).

I confess to an utterly zany fascination with this tome, though I cannot read through it for more than 20 minutes before a deep, trembling fear grips me and I feel like the perpetually panic-stricken Ismail Yassin when he says, “Ya mama!”

I confess to an utterly zany fascination with this tome, though I cannot read through it for more than 20 minutes before a deep, trembling fear grips me and I feel like the perpetually panic-stricken Ismail Yassin when he says, “Ya mama!”The Penal Law makes it seem as if anything is potentially criminal. There’s the notorious Article 48 on criminal conspiracy, etched into the Code after the assassination of Prime Minister Boutrus Ghali by the young pharmacology student Mahmoud al-Wardani in 1910. In his 1910 Annual Report, Lord Cromer’s successor Sir Eldon Gorst assured British parliamentarians, “The investigation of this case showed that the Egyptian Government did not possess sufficient power to deal with conspiracies for the commission of illegal acts, and that certain other measures were also necessary, especially as regards the section of the Code dealing with press offences, to repress evils which had manifested themselves during these proceedings. Laws…were therefore passed without delay to remedy these legislative defects.”

Article 48 was worded in such a way as to offer authorities maximum leeway in criminalising any action of which they did not approve. It essentially allowed police to detain any two people talking to each other on a street corner. After all, they could be deviously conspiring to commit a crime, even if no actual crime has been committed. Predictably, the Article proved very serviceable for subsequent rulers. In 2001, Professor Saad Eddin Ibrahim and his fellow defendants were accused of criminally conspiring to bribe television officials to air positive programming on Ibrahim’s research centre. While convicting Ibrahim on other charges, the court rejected this particular charge, without explanation. Fortunately for all Egyptians, a few days later (in a separate case) the Supreme Constitutional Court deemed this notorious Article unconstitutional. It is a matter of bitter irony to me that one of the principal architects of the sham legal case against Saad Eddin Ibrahim, the deeply unpopular and disreputable Maher Abdel Wahed, is now, incredibly, the Chief Justice of the sadly extinguished Supreme Constitutional Court.

Let’s continue on our pleasant little stroll through the Egyptian Penal Code, shall we? Section II Chapter 7 of the Code is all about Resisting Rulers and Not Obeying their Orders and Assaulting them with Slander and Other Means (actual title). Chapter 13 has everything you wanted to know about Obstructing Communications (including some specific charges levelled at the pro-democracy demonstrators). If you’re interested in how you can criminalise worker strikes and sit-ins, kindly turn to Section II Chapter 5 and Section III Chapter 15. Section III Chapter 7 enumerates the ways and means of slander and libel, including harassing a female in public (Article 306(bis), while Chapter 12 deals with gambling and lottery-related crimes (what on earth?!....). Finally, Section IV is a comprehensive list of petty violations such as throwing trash in the Nile, siccing dogs on others (such as police who sic dogs on peaceful protestors?), and causing a ruckus at night that disturbs the neighbours (good to know next time the crazy upstairs neighbours start screaming insanely at 4 am).

Harming the Government and Other Misdemeanours

Of course, Penal Codes are by definition…punitive! But the issue is how crimes are conceived and worded, and whether they’re added through the proper parliamentary channels after careful debate, or rather smuggled in by executive diktat when parliament is in recess. Given the ubiquity of Articles enumerating crimes against the government and their linguistic elasticity, it’s obvious that the Penal Code is a palimpsest of successive rulers’ efforts at political control rather than a compendium of international “best practices” in criminal legislation, as the government routinely claims. If anything, as the much-mourned and sorely missed Nabil al-Hilali taught us, Egyptian criminal provisions have more often than not copied international worst practices.

Take Article 98(A), levelled at Egyptian communists in 1979. It stipulates punishment of 10 years’ imprisonment for “anyone who establishes, organises, or steers organisations aiming to impose the control of one social class over others or aims to eliminate a social class or seeks to subvert the state’s social or economic foundations.” As Hilali explained, the Egyptian importers of the offending Article admitted that it was copied from a fascist law promulgated by Mussolini in 1930 to combat communists. After an aborted attempt by Ismail Sidqi to add the Article to the Penal Code in 1946, it was successfully included by Gamal Abdel Nasser soon after the March crisis of 1954 and the assassination attempt in Alexandria’s Manshiyya square.

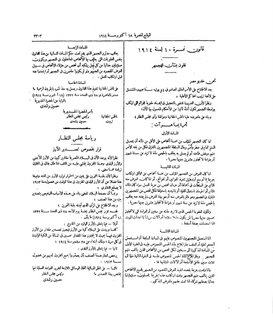

Another infamous legal product of rulers’ will to power is the notorious Article 80(d), added to the Penal Code in 1957 as part of a package of “crimes and misdemeanours emanating from abroad harmful to government security,” (left). The Article stipulates imprisonment for “every Egyptian who intentionally disseminates abroad false news, reports, or rumours on domestic conditions, with the result of weakening the financial confidence in the state.” The legislation was in part a response to the landed, anti-Nasser Abul Fath family and their radio station “Free Egypt Broadcasting” (Idha’at Misr al-Hurra), which disseminated material critical of the Egyptian regime from Beirut during the 1956 tripartite aggression. The Article remained buried in the Code unused until Mubarak’s legal henchmen found it useful and invoked it against sociologist Saad Eddin Ibrahim in 2001 and 2002, for allegedly “tarnishing the state’s image abroad” with his research on the status of Egyptian Copts.

Another infamous legal product of rulers’ will to power is the notorious Article 80(d), added to the Penal Code in 1957 as part of a package of “crimes and misdemeanours emanating from abroad harmful to government security,” (left). The Article stipulates imprisonment for “every Egyptian who intentionally disseminates abroad false news, reports, or rumours on domestic conditions, with the result of weakening the financial confidence in the state.” The legislation was in part a response to the landed, anti-Nasser Abul Fath family and their radio station “Free Egypt Broadcasting” (Idha’at Misr al-Hurra), which disseminated material critical of the Egyptian regime from Beirut during the 1956 tripartite aggression. The Article remained buried in the Code unused until Mubarak’s legal henchmen found it useful and invoked it against sociologist Saad Eddin Ibrahim in 2001 and 2002, for allegedly “tarnishing the state’s image abroad” with his research on the status of Egyptian Copts.And yet for all that, the Penal Code is not without some unexpectedly promising provisions. Section II Chapter 6 for example is all about public officials’ maltreatment of citizens. Article 129 specifies one year imprisonment or an (admittedly paltry) £E200 fine for any functionary who “relying on his position uses cruelty with the people in a manner that violates their honour or causes pain to their bodies.” Sounds like the perfect answer to Mubarak’s legion of torturers. But here’s the rub: While Article 126 stipulates a jail term of 3-10 years’ hard labour for any government agent utilising torture, its definition of torture is confined only to cases where the torture is applied to extract a confession, eliding the myriad cases of abuse inflicted for other purposes or for no purpose at all. Rights groups have long advocated a minimum of five years’ hard labour and the amendment of Article 126 to make the definition of torture consistent with Article 1 of the Convention Against Torture. The bitter irony here is that Egypt was the first Arab state to accede to the Convention, in 1986.

Crimes Occurring via Newspapers and Other Means

(such as Insulting the Ruler)

All of these crimes and we’ve yet to discuss the mother of them all: insulting the ruler. This particular offence falls within the infamous and forever controversial Section II, Chapter 14 of the Code titled: Crimes Occurring via Newspapers and Other Means, which enumerates in painstaking detail all the dastardly deeds that newspapers are inclined to. Perhaps the most persistent and outrageous provision in this Section is Article 179, first dubbed “Offence to the Monarchical Self” when Egypt was a monarchy. It stipulated imprisonment of up to five years for anyone “who causes offence to the royal self,” the queen, the heir to the throne, or regents. What’s more, the punishment was doubled if the offence occurred in the presence of any of the above! As our friend Sayed Ashmawi has colourfully shown, this was a particularly popular charge in the late 1940s and early 1950s, when the royal family came in for increasingly biting criticism from feisty newspapers and popular political forces.

Instead of being relegated to the trash bin of the royalist past after the republican transition in 1953, the Article’s language was simply amended in 1957 to read “insult the president,” and punishment was reduced to imprisonment for one year. And so it remains on the books to this day, yet invoked only once: against the people’s bard Ahmad Fu’ad Nigm in 1978 for mocking Anwar Sadat in his poem, “An Important Announcement,” (Bayan Ham). The Article remained dormant from 1978 until spring 2006, when the State Security Prosecution charged the peaceful demonstrators with, among other unforgivables, insulting the president of the republic through open defamation and slander (horrors!)

As if the very term “insulting the president” is not surreal enough and juridically nonsensical, last month there was an even more bizarre twist when the Warraq Misdemeanours Court invoked this Article and sentenced three ordinary citizens to one year in prison. The details are familiar by now. Citizen Said Muhammad Abdallah did what dozens of ordinary citizens do every day: he sued the president qua president, as per Article 68 of the Constitution guaranteeing resort to the courts as a basic right. His case was accepted by the administrative courts under number 3019/60th JY. al-Destour reporter Sahar Zaki reported on the suit, which though routine did have the distinction of targeting Hosni Mubarak personally for misuse of public funds and other abuses of power. But it’s common for newspapers to report on the filing of interesting, unusual, significant, or simply frivolous suits, particularly if they involve those in power as defendants.

The truly irregular aspect in all this is that seven individuals in the same neighbourhood of Warraq, hearing of Abdallah’s suit, took it upon themselves to sue him, Ibrahim, and Zaki for “insulting the president” and “intentionally broadcasting news or false rumours that disturb the public peace or strike fear in the people or harm the public interest,” (Penal Code Article 102bis). Though the plaintiffs had no standing (locus standi), and it is wholly unclear what action they were asking the court to rule on, lower court judge Osama Salah ruled for them. Unusually, he also went much further, castigating journalists for abusing the generous doses of freedom provided for them by the president.

Its oddity and legal dubiousness aside, the case underlines the nefarious contents of the Penal Code. A quick glance through Section II Chapter 14 reveals the extensive tools available for those in power to perfectly legally silence the advocates of the adversarial (if not yet investigative) press. Prison sentences abound for anyone who insults or defames a foreign king or president (Art. 181), an agent of a foreign government residing in Egypt (Art. 182), parliament, the military, the courts, or public agencies (Art. 184), and public servants or representatives (Art. 185).

The government’s proposed amendments to these and other offences is nothing but a manoeuvre designed to stem the tide of intensifying opposition and press scrutiny of powerholders’ wealth and assets. Instead of the current punishment of a monetary fine and 2-5 years’ imprisonment for slandering a public official (Art. 303), the government’s proposal is gaol time not to exceed 2 years or a fine of £E15,000-30,000. Journalists have long demanded the complete abolishment of imprisonment for ‘press offences,’ and a maximum amount of £E10,000 for fines.

Mafeesh Fayda v. The Spirit of Nabil al-Hilali

Just as it did with the amendments to the judiciary law, the government this week will surely ram through parliament the press-related amendments to the Penal Code, thus further fortifying the legal infrastructure of authoritarian rule. It’s nothing we haven’t seen before. Just think back to Anti-Terrorism Law 97/1992, Professional Associations Law 100/1993, replacing bottom-up election of university deans and village mayors with top-down appointment in 1994, Press Law 93/1995, and NGO Laws 153/99 and 84/2002. Just as with all of these previous laws, there will surely be valiant stands by individual, honourable members of parliament.

There will be street protests, strikes, sit-ins, and emergency general assemblies. There will be considerable furore in the press. And there will be many futile meetings with the entertaining Mr Fathi Sorour, who is a picture to behold with his ravishing comb-over, shameless sophistry, and generalised air of thorough venality and inanity.

There will be street protests, strikes, sit-ins, and emergency general assemblies. There will be considerable furore in the press. And there will be many futile meetings with the entertaining Mr Fathi Sorour, who is a picture to behold with his ravishing comb-over, shameless sophistry, and generalised air of thorough venality and inanity.The current stand-off between the government and organised sectors of society isn’t some unexpected “clampdown” or “backtracking on reform” (by the way, I’d love to meet this fetching Mr Government Reform if anyone can introduce him to me). Let’s not be silly and parrot this most repeated and meaningless take on current developments, then raise up our hands and exasperatedly cry “mafeesh fayda!” (as Saad Zaghloul is supposed to have said) simply because the rulers have got their way. No one in their right mind expected judicial independence to be actuated this spring, or a robust and effectively protected Fourth Estate to materialise this month. It’s not just that these are long-drawn out, marathon battles that span out over decades, nor that they rarely conform to neat little storylines with satisfying endings and unambiguous “outcomes,” nor even that large, dramatic transformations are wrought from small, obscure struggles.

It’s that there’s intrinsic value in understanding the details of large power plays, to honouring those who toil in obscurity to fight this or that repressive law, to appreciating those who sue the president to make a point, and recognising those parliamentary deputies who vote against an unjust bill that they know for certain will be passed, and standing in awe of those voters who brave tear gas and rubber bullets to record their choice. I’ve never heard any of them utter the dismissive, indifferent, and offensive “mafeesh fayda.”