A “democracy with fangs.” Mr Anwar Sadat’s unparalleled description of 'his' no-nonsense kind of democracy immediately came to mind this week as the curtain dropped on the second Act of parliamentary elections. In some districts, thugs hired by ruling party candidates attacked voters while police looked on or looked the other way. In others, police actively blocked access to polling stations and skirmished with fearless voters. In this district in Qalyoub (left), determined voters secured a rickety ladder to scale the back wall of a polling station closed off by security forces. An Alexandria voter’s depiction is arresting: “The police are like the Israelis and we are like the Palestinians. We are oppressed.”

A “democracy with fangs.” Mr Anwar Sadat’s unparalleled description of 'his' no-nonsense kind of democracy immediately came to mind this week as the curtain dropped on the second Act of parliamentary elections. In some districts, thugs hired by ruling party candidates attacked voters while police looked on or looked the other way. In others, police actively blocked access to polling stations and skirmished with fearless voters. In this district in Qalyoub (left), determined voters secured a rickety ladder to scale the back wall of a polling station closed off by security forces. An Alexandria voter’s depiction is arresting: “The police are like the Israelis and we are like the Palestinians. We are oppressed.”  Still, the outcome has seen startling gains for the Muslim Brothers (29 seats this stage, 76 overall) and a stinging drubbing for Hosni Mubarak’s party and regime. I doubt anyone predicted the utterly astonishing events unfolding before our eyes these days, though I don’t doubt we’ll soon hear from those who’ll claim they’ve known it all along. Be that as it may, I am amazed by the element of surprise in all this. Most surprising of all is the tenacity and fearlessness of some Egyptian voters. Unfazed by knife- and stick-wielding thugs, intimidating police formations shooting rubber bullets and tear gas, and the sheer logistical hurdles and sense of doubt accompanying the act of voting, ordinary men and women have trudged to polling stations to demand their rights.

Still, the outcome has seen startling gains for the Muslim Brothers (29 seats this stage, 76 overall) and a stinging drubbing for Hosni Mubarak’s party and regime. I doubt anyone predicted the utterly astonishing events unfolding before our eyes these days, though I don’t doubt we’ll soon hear from those who’ll claim they’ve known it all along. Be that as it may, I am amazed by the element of surprise in all this. Most surprising of all is the tenacity and fearlessness of some Egyptian voters. Unfazed by knife- and stick-wielding thugs, intimidating police formations shooting rubber bullets and tear gas, and the sheer logistical hurdles and sense of doubt accompanying the act of voting, ordinary men and women have trudged to polling stations to demand their rights. There is something deeply noble to me about this lone citizen trying to negotiate her way into this formidably fortified Alexandria polling station. Let me be clear and honest: if I were subject to the levels of intimidation and physical abuse that many voters endured, I would have paused for a very long time before venturing out of the house. Being an intellectual, I would surely overanalyse my fear and craft it into some pseudo-argument for why voting is futile in the first place. But, you see, the vast majority of Egypt’s people don’t have the luxury of overanalysing anything. Their life circumstances are much more pressing. The act of voting for them is a matter of survival and dignity. Says Alexandria voter Mustafa Rizk, “We all hate the government. They treat us like animals. It’s not Islamic the way they treat people. This is why we all want an Islamic government.”

There is something deeply noble to me about this lone citizen trying to negotiate her way into this formidably fortified Alexandria polling station. Let me be clear and honest: if I were subject to the levels of intimidation and physical abuse that many voters endured, I would have paused for a very long time before venturing out of the house. Being an intellectual, I would surely overanalyse my fear and craft it into some pseudo-argument for why voting is futile in the first place. But, you see, the vast majority of Egypt’s people don’t have the luxury of overanalysing anything. Their life circumstances are much more pressing. The act of voting for them is a matter of survival and dignity. Says Alexandria voter Mustafa Rizk, “We all hate the government. They treat us like animals. It’s not Islamic the way they treat people. This is why we all want an Islamic government.”

In the same vein, I like Tom Perry’s pithy and perceptive lead, “The deep, filthy puddles in the streets leading to Belkina's polling station remind some villagers to vote against Egypt's rulers when they get there.” It is rather straightforward, is it not? Egyptian voters, forever falsely said to be apathetic, tribal, apolitical, and a thousand other derisive adjectives, are wresting their right to be heard and to demand their basic right to a human standard of living. It is they who are responsible for the Ikhwan’s success; it is they who have wrought the ruling regime’s deafening failure; it is they who constantly upend and confound the hectares of useless print purporting to “analyse” them. The Ikhwan have done well to take voters and their needs seriously, and voters in turn are returning the favour by braving security phalanxes and demanding their right to be heard (above). Now I am deeply ambivalent about the Ikhwan, but who cares? As my Egyptian politics guru rightly reminds (that’s right, guru), one cannot impugn their fundamental respect for the ordinary Egyptian, and their superior skills at capitalising on and augmenting seemingly puny opportunities. They are not infallible and they are not without schisms, but they are committed. And they are clean.

The Ikhwan have done well to take voters and their needs seriously, and voters in turn are returning the favour by braving security phalanxes and demanding their right to be heard (above). Now I am deeply ambivalent about the Ikhwan, but who cares? As my Egyptian politics guru rightly reminds (that’s right, guru), one cannot impugn their fundamental respect for the ordinary Egyptian, and their superior skills at capitalising on and augmenting seemingly puny opportunities. They are not infallible and they are not without schisms, but they are committed. And they are clean.

So before the pundits begin to produce their post-mortems, moaning and wailing about the supposedly sinister rise of the Ikhwan, let’s be honest and clear-headed here. The Egyptian public is not some drugged mass following the siren song of religion. The Egyptian public is suffering from a regime that is aloof and inept at the very best and dangerous and violent the rest of the time. It is not a mystery nor a ‘problem’ how an uncorrupt, moralising, problem-solving, and politically astute organisation has captured the provisional trust of large swathes of that public. The challenge for the Ikhwan as a political phenomenon will be to maintain and truly live up to voters’ trust. No easy task, and not a foregone conclusion.

Good dramas always feature a stirring contest between a roguish villain and a sympathetic underdog. The election’s second Act furnished us just that in the hateful presence of Mustafa al-Fiqqi and the admirable figure of Gamal Heshmat. For background, read the backstory on Fiqqi here. I’m too revolted by him at present to waste precious narrative space on his uncanny resemblance (literal and figurative) to a lowly troll. Heshmat on the other hand is the picture of a true believer. Not a zealot, but an indefatigable striver. In a democratic Egypt, he would be a very successful national politician, with a long and productive career. His secret: a keen sense of constituents’ needs in his native Damanhour. A former Nasserist, Heshmat is among the new breed of Ikhwan for whom Islamist sermonising works hand in glove with age-old constituency service. Simple as that. The man is intelligent, affable, and accessible. Having the repulsive Fiqqi “run” against Heshmat on his home turf of Damanhour must go down as one of the most colossally stupid ideas in contemporary Egyptian political history. I repeat: the author of the idea deserves special plaudits for political inanity and profoundly inept strategic planning. Heshmat and his supporters campaigned intensely. By contrast, the London-loving Fiqqi made a few perfunctory rounds, letting it be known that he’s the “presidency’s candidate.” As expected, on November 20, Damanhouris said Toz. They braved security forces' determined blocking of roads to polling stations (above) to return their man, buoyed by the government's unjust ousting of him from parliament in 2003. That’s the beauty of Egyptians at election time, they say Toz loud and clear to anyone who will listen. Heshmat put Fiqqi in the shade, with a staggering 24,611 votes to Fiqqi’s 8,606. In an exact replay of the Doqqi district fiasco, presiding legal officers panicked and whispered of the dire consequences of a Fiqqi defeat. Presidential representatives monitored the vote count by mobile phone, sending desperate entreaties on the importance of returning Fiqqi as chair of the Foreign Affairs committee in parliament at this “critical time for Egypt,” or some such hogwash. In a flagrant bait-and-switch, after a vote count with absolutely no traces of ambiguity, legal officers announced Fiqqi’s victory and Heshmat’s defeat.

Heshmat and his supporters campaigned intensely. By contrast, the London-loving Fiqqi made a few perfunctory rounds, letting it be known that he’s the “presidency’s candidate.” As expected, on November 20, Damanhouris said Toz. They braved security forces' determined blocking of roads to polling stations (above) to return their man, buoyed by the government's unjust ousting of him from parliament in 2003. That’s the beauty of Egyptians at election time, they say Toz loud and clear to anyone who will listen. Heshmat put Fiqqi in the shade, with a staggering 24,611 votes to Fiqqi’s 8,606. In an exact replay of the Doqqi district fiasco, presiding legal officers panicked and whispered of the dire consequences of a Fiqqi defeat. Presidential representatives monitored the vote count by mobile phone, sending desperate entreaties on the importance of returning Fiqqi as chair of the Foreign Affairs committee in parliament at this “critical time for Egypt,” or some such hogwash. In a flagrant bait-and-switch, after a vote count with absolutely no traces of ambiguity, legal officers announced Fiqqi’s victory and Heshmat’s defeat.

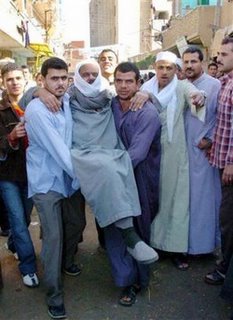

The plot thickens when a fascinating deus ex machina swoops down on the scene, in the guise of an upstanding legal officer by the name of Noha al-Zeiny. She decides to tell the truth regardless of the consequences, and hands over her candid testimony to al-Misri al-Youm, where it’s published on Thursday (full text here). “I use this forum to bear witness to what I learned, of the falsifying of election results in the first district in Damanhour,” she writes, “And I call on those who witnessed the incident to offer up their testimony as well. One of them said to me afterwards that he could not sleep after what happened.” The irony of ironies is that al-Zeiny is not even a sitting judge but a high-ranking member of the Administrative Prosecution, legal officers the government expressly counted on to facilitate its election doctoring. What will the third Act bring? We must wait and see. But I know one thing for certain. It will usher in more surprises, made by human beings for whom voting is an act of defiance, and perhaps even a matter of honour. This disabled Qalyoub man is being assisted to a polling station to vote on November 26. A Tanta voter’s measured expression of outrage to al-Jazeera haunts me: “Security is preventing all the citizens from entering the polling stations, as you can see. Is this right? Does the president of the republic agree to this? Let him call the supervisor of the polling station to let people in, or then let us go home!”

What will the third Act bring? We must wait and see. But I know one thing for certain. It will usher in more surprises, made by human beings for whom voting is an act of defiance, and perhaps even a matter of honour. This disabled Qalyoub man is being assisted to a polling station to vote on November 26. A Tanta voter’s measured expression of outrage to al-Jazeera haunts me: “Security is preventing all the citizens from entering the polling stations, as you can see. Is this right? Does the president of the republic agree to this? Let him call the supervisor of the polling station to let people in, or then let us go home!”

*Photos from AP, AFP, Reuters.