I will always remember 2005 for its abundant surprises and endless ferment, with not a single dull moment, not even a lull. It’s a year too eventful for the inevitably boring and perfunctory exercise of the year-in-review, yet too rich to let pass without some sort of stock-taking. A year unthinkingly dismissed as a ‘disappointment’ by contrarians, cynics, and busybodies who prattle too much and think precious little.

I will always remember 2005 for its abundant surprises and endless ferment, with not a single dull moment, not even a lull. It’s a year too eventful for the inevitably boring and perfunctory exercise of the year-in-review, yet too rich to let pass without some sort of stock-taking. A year unthinkingly dismissed as a ‘disappointment’ by contrarians, cynics, and busybodies who prattle too much and think precious little.Cataloguing the many events of the year would be tedious and unimaginative, mish keda? I want to instead emphasise three “persons” who made 2005 rather exceptional. First, the Egyptian Judges Club, Nadi Qudat Misr, a wondrously unlikely space of incessant mobilisation. Second, Kifaya, a wondrously unlikely impulse of political innovation. And finally, the recruits of the Central Security Forces, those fearsomely helmeted and armed human beings omnipresent on Egyptian streets, more than ever in 2005. Judges, activists, and gendarmes. Together and separately, they shaped 2005.

1

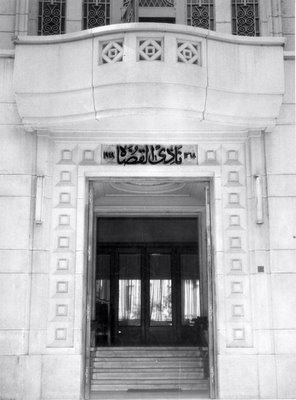

The Egyptian Judges Club is a remarkable institution. Founded in 1939 as a collective of judges adamant about a new law for the judiciary (eventually promulgated in 1943), it continues to aggregate and organise judicial opinion, and continues to agitate for a new law guaranteeing the true independence and professionalism of the judicial branch. The Club’s pivotal role in 2005 comes as no surprise to the judges themselves, whose robust collective memory is stacked with proud moments of defiance and resolve: 1951, 1963, 1968-69, 1984, 1990-91, 2004, and 2005.

The Egyptian Judges Club is a remarkable institution. Founded in 1939 as a collective of judges adamant about a new law for the judiciary (eventually promulgated in 1943), it continues to aggregate and organise judicial opinion, and continues to agitate for a new law guaranteeing the true independence and professionalism of the judicial branch. The Club’s pivotal role in 2005 comes as no surprise to the judges themselves, whose robust collective memory is stacked with proud moments of defiance and resolve: 1951, 1963, 1968-69, 1984, 1990-91, 2004, and 2005.The Club’s general assemblies in 2005 were, without exaggeration, historic events, and I hope their videotaped proceedings are circulated for a much wider and fuller viewing than the snippets aired on al-Jazeera. But what on earth is a general assembly? It’s the supreme deliberative and law-making body of a particular institution, comprising all its members. Historically, the general assemblies of Egyptian professional guilds have been paradigms of direct democracy, featuring real debates, virulent disagreements, hefty doses of humour, utter chaos, ego wars, adamant majority rule, and vocal protests by the minority. Sometimes, general assemblies have seen inspiring displays of oratory and heroism. Sometimes, they were witness to startling instances of shameless quackery. Always, they were an arena for brinkmanship and the clash of competing interests. Direct democracy.

It’s no surprise then that Egypt’s rulers have always sought to control and infiltrate professional unions’ general assemblies, from King Farouq all the way down to the current embattled ruler and his entourage. The control attempts are that much more fascinating when the general assembly in question is composed of state officials, and all the more delectable when those state officials have a tradition of convening contentious general assemblies that threaten the vital interests of the power-hungry executive.

The Judges Club general assemblies in 2005 were a nightmare for Mubarak and his lieutenants. On April 18 in Alexandria and then May 13, September 2, and December 16 in Cairo, judges not only subjected the regime to measured but devastating criticism in full view of local and international media. They also threatened to complicate a very sensitive procedure that Mubarak and Co. were very nervous about: elections. Now there have always been judicial rumblings every time an election rolls around. But in 2005, the judges took everyone by surprise when they turned rumblings into concrete and effective mobilisation. Most surprised were the Mubaraks and their minions in the Supreme Judicial Council and the Ministry of Justice, who still don’t know what to do with the adamant judges.

The 2005 general assemblies were also occasions for a highly significant yet almost imperceptible process. They politicised, inspired, and perhaps even radicalised younger judicial cadres, led by a charismatic and delightfully plain-speaking contingent from Alexandria. These younger judges clinched the victory of Zakariyya Abdel Aziz as chairman on December 16 and re-elected Mahmoud al-Khodeiry to a second term in Alexandria a week later. As their long serving elders gradually retire from the scene, the younger judges will steer the battle in its next phase, armed with less patience, closer ties to the judicial rank and file, newer ideas for redrawing executive-judicial relations, clearer concepts for more effective action, and most important: less fear. “Do your utmost,” they say to the executive’s legal henchmen and inept fixers. “We are not afraid.”

Nadi al-Quda’s struggle for a new judiciary law and full supervision over the electoral process did not begin nor end in 2005. That year was merely a particularly meaty chapter, to be continued over the next several years, and still in its full throes as I write this. But the truly new element introduced in 2005, aside from the relinquishing of fear, is the new affinity between judges and activists that made itself especially clear on May 13 and September 2. When judges signalled at the beginning of the year that they would have no truck with falsifying voters’ will in elections, Kifaya and Muslim Brother activists quickly cleaved to the judges and protested more than once in solidarity with their demands.

Judges in turn relished the public support and cultivated it as a key asset in their negotiations with the executive. And so a new alliance was made, one that al-Ahali journalist Tharwat Shalabi neatly captured in December when he dubbed Nadi al-Quda the new Beit al-Umma. Presumptive veteran journalist Sana’ al-Beesy shamelessly cribbed Shalabi and pilfered the credit for the evocative metaphor, so let’s set the record straight and return the credit to its rightful bearer.

2

There’s no doubt that Kifaya was one of the main architects of heightened public consciousness of and support for judicial independence. But it did much more. A movement-idea that was subjected to incessant criticism from the day it was born, Kifaya muddled right on through, organising the summer Wednesday demonstrations that were finally capped by the “Batil!” protest of September 10, before all the relevant parties turned their attention to the battle of parliamentary elections. If wresting the right to collective street protest was all that Kifaya did, it would have been remarkable enough.

There’s no doubt that Kifaya was one of the main architects of heightened public consciousness of and support for judicial independence. But it did much more. A movement-idea that was subjected to incessant criticism from the day it was born, Kifaya muddled right on through, organising the summer Wednesday demonstrations that were finally capped by the “Batil!” protest of September 10, before all the relevant parties turned their attention to the battle of parliamentary elections. If wresting the right to collective street protest was all that Kifaya did, it would have been remarkable enough.

But it did more. Kifaya spurred all sorts of groups to form spin-offs (Youth, Artists, Journalists, Lawyers, and Doctors, all For Change). It jolted the Ikhwan behemoth out of its satisfied complacency as the prime opposition force. It infuriated police chiefs and their superiors and threatened the gerontocracy running the “opposition parties.” It alternately flummoxed and tempted a broad spectrum of international observers, not least the journalists and editors of the American Washington Post, who rather ingeniously found a way to credit George W. Bush for Kifaya’s existence (smashing, no?). Like the Judges Club, Kifaya confounded all its interlocutors while compelling them to radically reorder their plans.

I can’t resist mentioning those who were acutely perturbed by the movement. Gamal Hosni Mubarak and his daddy and their mercenaries first tried to dismiss Kifaya as a handful of foreign agents parachuting in on dear Egypt. Then they dispatched their house intellectuals to dub Kifaya a “TV phenomenon” with no representational clout. But then their British and American political consultants alerted Gamal and daddy that attacking Kifaya was inappropriately gauche and a tad thuggish (oh dear). The handsomely rewarded image-makers thus instructed that it was much sexier for the Gamal Mubarak product (90% foreign-made, the remainder pure local knavery) to appropriate the energy and rhetoric of the movement.

So the dutiful Mubaraks, confident that the aganeb are always right, abruptly shifted gears. They went around waxing lyrical about how the “Cairo Spring” was a marvellous thing, how dearest Egypt would never be ruled in the same bad old ways again, how the NDP had a spanking new plan to transport Egypt to blissful heights of prosperity and freedom. Gamal’s friends pitched in to help, declaring that Kifaya’s mere existence was a sure sign of the uniquely benevolent and open-minded temperament of Egypt’s current rulers. Ahhhh, the chicanery.

Outside the halls of illegitimately acquired political power but keen on remaining on its good side, a whole cottage industry sprung up to pooh-pooh the very idea of Kifaya. “They should stop cursing the president, ‘ayb” they frowned. “They’re a bunch of failures and leftist has-beens who desperately want the limelight,” they smirked. “What is their vision?” they demanded. “Can they do anything else but demonstrate?” they wondered. “They’re so disorganised.” “They’re anti-Mubarak, but what are they for?” “They’ll never be able to run the country!” “Who’s behind them? I don’t trust them.” “It’s a handful of intellectuals, they don’t have any popular support.” “What is this silly term, “Kifaya”? Shouldn’t they come up with a more respectable name?” “And those girls who go to their protests, of course they’re going to be attacked, what do they expect?”

I count myself among those who are deeply inspired by this thing called Kifaya. I respect those who have serious and insightful critiques of the movement, but I have nothing but scorn for those who cloak their hatred and fear as serious critique. As a social movement compared to others in Egyptian history and the history of other countries, Kifaya is a tiny and precarious creature, with its share of blunders and factionalism.

But I still love it. For having the courage and decency to say enough, however feebly. For weathering physical injury and abuse to make a point. For not succumbing to the pernicious myths about Egyptians’ (and Arabs’) masochism. For trying to do something constructive and noble despite the formidable odds. For reminding us of the power and value of a quixotic act. And for laying the groundwork for collective action despite intense political, tactical, and personal disagreements, all in a political environment fraught with risk and danger. Above all, I love it for working to dismantle the fear implanted in the majority of Egyptians by decades of repression, deprivation, and rotten ideas.

Believing in Kifaya may or may not be like believing in the efficacy of hurling an egg at a stone. It does mean believing in an urgent recovery of civil citizenship, what the movement articulated with its two-day conference of 3-4 January. As sectarian conflict flares up with disturbing regularity, huge class inequalities deepen by the day, the very notion of the public weal is completely eroded, the state has ceased to protect and instead attacks citizens, and a generalised malaise engulfs even the most microscopic interpersonal relations, how could it not be patently obvious that regaining our citizenship is a matter of the absolute highest urgency?

Kifaya, the Ikhwan, Ayman Nour, Freedom Now, unaffiliated leftists and Islamists: all in their own ways have chosen the path of resistance and refusal to accept our lot. So have genuine liberals, not phony government hacks and certainly not two-bit entrepreneurs who’ve found in “liberalism” a fancy cover for their achingly embarrassing scribblings (the Tarek Heggi and Mohamed Salmawy crowd). Kifaya gathers all these people under its big, rickety, but protective umbrella. I’ll cleave to it any day, warts and all.

3

Nothing symbolises the state of eroded citizenship more poignantly than the plight of the Amn al-Markazi soldier, what the late masters Atef al-Tayyeb and Ahmed Zaki presciently foretold with their unforgettable character Ahmad Sab’ al-Layl in al-Baree’ (The Innocent One). The year 2005 offered unprecedented opportunities for traffic between the Central Security Forces and activist citizens. I like to think that this was an eye-opening experience for at least some recruits, but I don’t know. What I know is that their swollen ranks and sub-human living conditions are constant reminders of the depths of exploitation and injustice in this country, one of the many tragedies created by Hosni Mubarak’s regime that will take us decades to clean up.

Nothing symbolises the state of eroded citizenship more poignantly than the plight of the Amn al-Markazi soldier, what the late masters Atef al-Tayyeb and Ahmed Zaki presciently foretold with their unforgettable character Ahmad Sab’ al-Layl in al-Baree’ (The Innocent One). The year 2005 offered unprecedented opportunities for traffic between the Central Security Forces and activist citizens. I like to think that this was an eye-opening experience for at least some recruits, but I don’t know. What I know is that their swollen ranks and sub-human living conditions are constant reminders of the depths of exploitation and injustice in this country, one of the many tragedies created by Hosni Mubarak’s regime that will take us decades to clean up.

Though composed for an entirely different context to salute an entirely different class of soldier, Nigm and Imam’s beautiful tune always rings in my ears when I see the CSF recruits, idling together on some residential street, waiting for their next assignment to put down noble protestors or attack unarmed refugees. Like the great Kamal Khalil, I’ll never be able to see the recruits as willing accomplices in state violence, but downtrodden and violated human beings. Their emancipation is inseparable from the struggle for effective representation and real social justice in Egypt.

*Alf Shukr to the talented Mouaten Masri for the photograph of the CSF recruit.