Sonallah Ibrahim has become that rare novelist whose every new work is eagerly anticipated and turns into a literary event of note. His politics and his courage are only partly to account for this. It’s his knack for innovation and experimentation with new themes, new styles, and new methods for composing a novel that give Ibrahim a vitality rare among his contemporaries. Though all of his novels are written in an extremely shorn, reportorial prose allergic to any embellishment, and everything he writes involves some facet of human alienation from oppressive socio-political structures, his subject matter and methods have varied. That Smell (1966), The Committee (1981), and Zaat (1992) explore individual human alienation under political authoritarianism and capitalism; Star of August (1974) and Warda (2000) are more frankly political novels about concrete political struggles; Honor (1997) and Oases Diary (2005) chronicle the prison experience based on Ibrahim’s incarceration with other Communists from 1959-1964; Beirut Beirut (1984) and Amrikanli (2003) transcribe the rituals of daily life against the backdrop of civil war in Lebanon and late capitalism in America.

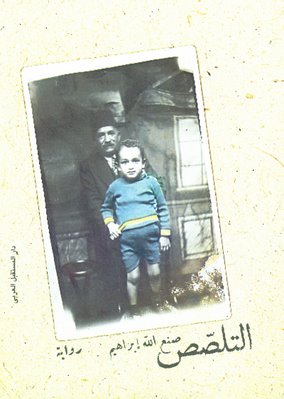

Sonallah Ibrahim has become that rare novelist whose every new work is eagerly anticipated and turns into a literary event of note. His politics and his courage are only partly to account for this. It’s his knack for innovation and experimentation with new themes, new styles, and new methods for composing a novel that give Ibrahim a vitality rare among his contemporaries. Though all of his novels are written in an extremely shorn, reportorial prose allergic to any embellishment, and everything he writes involves some facet of human alienation from oppressive socio-political structures, his subject matter and methods have varied. That Smell (1966), The Committee (1981), and Zaat (1992) explore individual human alienation under political authoritarianism and capitalism; Star of August (1974) and Warda (2000) are more frankly political novels about concrete political struggles; Honor (1997) and Oases Diary (2005) chronicle the prison experience based on Ibrahim’s incarceration with other Communists from 1959-1964; Beirut Beirut (1984) and Amrikanli (2003) transcribe the rituals of daily life against the backdrop of civil war in Lebanon and late capitalism in America. Ibrahim’s latest novel, Sneaking (2007), is his most intimate work yet, mining the author’s unconventional childhood to explore the fundamental human emotion of yearning: yearning for maternal love, for lost youth, for the simple creature comforts of domesticity. The novel is essentially a fictionalised account of the author’s childhood; the cover photograph depicts Ibrahim and his father, a very expressive image embodying the close-knit relationship between an ageing father and his growing son. It is this co-dependent, claustrophobic, yet touching relationship that forms the centrepiece of the narrative.

Born in 1937, Ibrahim was the only child from his father’s second marriage to a much younger nurse hired to tend to his ailing first wife. The 16-year-old nurse kept the husband company, read the newspapers, and talked with him about politics. The respectable, high-ranking civil servant fell in love for the first time in his life and married the nurse in secret. When the first wife died and Ibrahim’s father told his grown children of his second household, they became extremely upset and were cold and unwelcoming toward their half-brother, punishing him for his mother’s modest origins. These and more details unfold in the novel. Particularly remarkable is Ibrahim’s vivid reconstruction of his childhood feelings toward his snooty half-sister, a heartbreaking mixture of eagerness for love and acceptance and fascination by her comfortable bourgeois household.

In several ways, Sneaking bears Ibrahim’s trademark imprint: extremely short, clipped sentences that resemble note-taking more than narrative prose; an extraordinarily detailed, clinical rendition of the minutiae of daily life (down to the bedbugs plaguing the nine-year-old child); and a backdrop of momentous events, in this case the 1947-1948 ferment on Egyptian streets against King Farouq, the Zionist control of Palestine, and bickering political party leaders. But in its lyrical tone and familial setting, the novel is quite a departure from Ibrahim’s previous work. Returning to his childhood, the novelist delves into territory he has never mined (until the very recent Oases Diary).

As might be expected, Ibrahim’s take on childhood is original and unsentimental. There’s no nostalgia here, no rose-colored rendition of time and place, no attempt to juxtapose an idealised past against a grim present. Instead, there’s a gripping, child’s-eye view of the world by a child exceptionally attuned to the moods, habits, and silent yearnings of the adults around him. This child glides through life surreptitiously listening in on adult conversations that he’s not supposed to hear, adult behaviour he’s not supposed to see, adult longings he’s not supposed to understand. So listen, peek, and sneak he does. Indeed, the word talassus (sneaking) is peppered throughout the novel like an idée fixe, signalling the young child’s coming-of-age and induction into the adult world. By sneaking about in his own and others’ apartments and peeking from behind locked gates, the child sees and overhears adults napping, copulating, depilating, flirting, bathing, menstruating, cooking, cleaning, and performing other life cycle rituals.

Ibrahim has adopted a hallowed genre but given it a creative twist, writing a very quirky, intimate, offbeat, yet strangely affecting bildungsroman. Unlike the conventional form, however, his bildungsroman is as concerned with old age as it with youth. As the child’s eyes are opened to the wide adult world, the elderly father grows keenly aware of his own mortality and gradual receding from life. Like an old man, he ruefully reflects on his waning faculties and maintains a strict regimen of fussy rituals (including a hilarious scene where he imposes on the child a series of superstitious exercises designed to improve the latter’s performance on exams). One of the most touching scenes in the novel involves a conversation between the father and his randy friend Ali Safa in which Safa shares his obsession with his 16-year-old neighbour girl. The child, pretending to be lost in sleep, listens on in fascination as Safa relates his fantasies and bemoans his lost youth and his father tenderly recounts his love for his second wife and his joy at experiencing the true taste of fatherhood at a late age. While overhearing both men voice their longings, the child is prompted into his own reverie, remembering fragments of his happier past, of both parents joyfully singing together in a warm house filled with the comforting smell of frying food. The moving scene twines the deep desires of both young and old for feminine warmth and companionship, the theme that Ibrahim has identified as the dominant motif of his new novel.

The intensity of their longing is fuelled by the father and son’s cramped life on the father’s limited pension, renting out rooms in their apartment to save money and living together in one squalid, freezing room infested by bedbugs. The mother has disappeared from their life; the narrator hints that she is confined to a mental institution or has died. Both cope with her absence by clinging to and caring for each other while constantly yearning for a soft female presence. During their holiday visits to his uppity half-sister in Heliopolis, the child is fascinated by the cleanliness of her house, the softness and clean smell of her bedding, the tastiness of the food prepared by her cook. Everything around them reminds impoverished father and son of their emotional and material deprivation. Even when they return to their inevitably dark alley and draughty room in Abbasiyya, they encounter signs of others’ domestic comforts, overhearing their lodgers the constable and his young wife in their room laughing and singing along with love songs on the radio, empty plates of home-cooked food piled up on the dining table.

Stylistically, the novel includes several features that distinguish it from the previous Amrikanli’s mere transcription of daily life. The author signals the child’s longing with portions of bold text that describe his daydreams, vivid memories of his mother, and childhood ditties that remind him of happier years when she was present and his father was happy. Juxtaposing these portions from the past with the father and son’s present spartan existence is especially powerful in conveying the boy’s feelings of loneliness and longing. Words and images recur throughout the text to underscore central motifs and lend the novel structural coherence: the repetition of the word talassus; the inevitably dark alleyway to their house; their claustrophobic, fetid room with the hard bed pillows and ratty mattress.

Sneaking begins and ends with the father and son going about their daily rituals: buying their meagre groceries on credit, working together on the boy’s composition homework. The bond between an aged father and his nine-year-old son is the real subject of Sneaking, Sonallah Ibrahim’s most introspective work yet. This is not a novel about the combustible politics of the late 1940s, nor an account of the ravaging effects of capitalism on individual lives. It is a novel about the emotional world of ordinary people living in a particular time and place, pining for the small creature comforts that make life worth living.

“You’ll read it in a day and come back and buy copies for all your friends,” the bookseller said about Khaled al-Khamisy’s Taxi. He’s right about one thing: the book is impossible to put down (my friends will have to buy their own copies). It's a simple yet profound idea gracefully composed and artfully executed. At first, I cringed at the potential for condescension and cliché when collating the stories of Cairo’s cab drivers. The idea is brilliant, the product could be disastrous. I expected pages of patronising, hackneyed “analysis,” or moralising preaching, or superficial fare the sole purpose of which is to showcase the author’s brilliance. But from the first few pages, screenplay writer and political scientist Khaled al-Khamisy makes it perfectly clear that he’s an excellent listener and a faithful transcriber, with a fine ear for the comical, poignant, and tragic in the stories of the taxi drivers. In other words, the author thankfully does us the favour of withholding his judgment and refraining from lecturing as he conveys undoctored conversations brimming with humour, pathos, and startling insight.

“You’ll read it in a day and come back and buy copies for all your friends,” the bookseller said about Khaled al-Khamisy’s Taxi. He’s right about one thing: the book is impossible to put down (my friends will have to buy their own copies). It's a simple yet profound idea gracefully composed and artfully executed. At first, I cringed at the potential for condescension and cliché when collating the stories of Cairo’s cab drivers. The idea is brilliant, the product could be disastrous. I expected pages of patronising, hackneyed “analysis,” or moralising preaching, or superficial fare the sole purpose of which is to showcase the author’s brilliance. But from the first few pages, screenplay writer and political scientist Khaled al-Khamisy makes it perfectly clear that he’s an excellent listener and a faithful transcriber, with a fine ear for the comical, poignant, and tragic in the stories of the taxi drivers. In other words, the author thankfully does us the favour of withholding his judgment and refraining from lecturing as he conveys undoctored conversations brimming with humour, pathos, and startling insight.The book includes conversations with drivers from April 2005 to March 2006, a year when the author relied almost exclusively on cabs to move around the city. This exposed him to the extremely diverse human pool that now constitutes the capital’s modern coachmen. Anyone who uses taxis and pays any attention knows that there is no such thing anymore as the prototypical taxi driver (if there ever was). High unemployment and underemployment, skyrocketing costs of living, and a 1990s law allowing any aged vehicle to be turned into a taxi have all conspired to dramatically increase the number and diversity of taxis and their drivers (80,000 cabs in Greater Cairo alone, al-Khamisy says). Drivers now run the gamut from white-collar professionals to blue-collar workers to moonlighting civil servants to college students. They’re of varying age groups, from drivers in their late teens who’ve just secured a license to septuagenarians who started driving in the 1940s. A fair portion of drivers have postgraduate degrees, and all have stories to tell.

After a brief, nimble introduction, al-Khamisy proceeds to recount 58 encounters with drivers from all walks of life (including a creepy yet all too believable exchange between a cab driver and the author’s 14-year-old daughter taking a taxi alone for the first time). The stories are textured, atmospheric, and very diverse, ranging from descriptions of the bitter struggle to earn a few pounds driving a taxi in extremely adverse conditions, to drivers’ evocative memories and personal stories (especially touching is the film buff who had not stepped into a movie theatre for 20 years), to social critique and analysis (especially remarkable here are the driver who dissects the hidden function of television commercials, and the driver who has a stunningly insightful analysis of the eclipse of street protest in Egypt since 1977), to drivers’ poignant hopes and aspirations (the driver who daydreams about an African cross-continent trip).

One of the most remarkable, hilarious, and insightful set of stories are those about politics, especially those conversations that deal with Hosni Mubarak and his presidential elections. It is to al-Khamisy’s great credit here that he faithfully transcribes both those opinions for and against the perennial president, and by doing so he makes a subtle point: it is very misguided to generalise about Egyptian public opinion from a few dozen examples, or to treat taxi drivers as somehow “authentic” voices of “the street.” Mercifully, this kind of essentialism and faux-populism or whatever it is is completely absent from the book. For every foreign correspondent and “analyst” who thinks he’s located the “pulse of the Egyptian street” by exchanging a few words with his cab driver, al-Khamisy’s book is a powerful rebuke. Indeed, one of its great virtues is to rescue taxi-driver opinions from over-analysis and rescue taxi-drivers themselves from the burden of representing some hallowed, comforting, but nonexistent “everyman.”

A textured book takes you on a roller coaster of emotions. Reading Taxi makes one teary-eyed with laughter in one chapter and teary with anger in the next. Particularly enraging are taxi drivers’ stories of their harrowing encounters with predatory and corrupt police officers, and the related nightmare of being stopped for hours when Mubarak’s motorcades are passing through. In unforgettably straightforward detail, one driver relates his experience of being stopped for four hours on the Salah Salem road: “That day, I dropped off the taxi to its owner, gave him all I had, and promised to give him the rest the next day. I went home and I swear to you, we all slept without dinner. My wife and kids were waiting for me like every night for dinner, but I came back empty-handed. My wife cried and put the kids to sleep, and I sat by the window listening to Qur’an to calm myself down.”

A textured book takes you on a roller coaster of emotions. Reading Taxi makes one teary-eyed with laughter in one chapter and teary with anger in the next. Particularly enraging are taxi drivers’ stories of their harrowing encounters with predatory and corrupt police officers, and the related nightmare of being stopped for hours when Mubarak’s motorcades are passing through. In unforgettably straightforward detail, one driver relates his experience of being stopped for four hours on the Salah Salem road: “That day, I dropped off the taxi to its owner, gave him all I had, and promised to give him the rest the next day. I went home and I swear to you, we all slept without dinner. My wife and kids were waiting for me like every night for dinner, but I came back empty-handed. My wife cried and put the kids to sleep, and I sat by the window listening to Qur’an to calm myself down.” Lest the reader think al-Khamisy presents a one-dimensional view of taxi drivers as downtrodden, wronged beings, there are also plenty of encounters with drivers who are liars, bigots, crooks, and jerks. There are unscrupulous drivers who spin tall tales to garner sympathy and extract a higher fare; aggressive, preachy drivers who blast religious sermons at maximum volume; and drivers who prey on their weak, poor, and/or female customers. One of the most haunting vignettes in the book is an interaction between the author, a gruff cab driver, and a shoe shiner that still sends shivers down my spine every time I re-read it.

As anyone who makes heavy use of taxis knows, this mode of transportation is often occasion for unusually intimate, unintended, fleeting encounters, encounters that can be intensely regenerative or extremely upsetting. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that al-Khamisy begins and ends his book with two riveting, purgative encounters that carry loads of inexpressible meaning. The book opens with the story of an antique driver who has been driving a taxi since 1948, and ends with an absolutely magical encounter ten minutes before Ramadan iftar that prompts al-Khamisy to pen some of the most beautiful prose I’ve read in a long while: “He left me with the taste of sugar in my throat, and the scent of night musk in my soul, and he made me break my fast unhurriedly for the first time in a long time, contemplating everything around me…”

I can’t come up with a better descriptor for Taxi than Galal Amin’s blurb at the back of the book that “it’s like a refreshing breeze on a hot day.” Yes, the book is about the resilience of the human spirit, it is a powerful chronicle of the Herculean struggle for survival and dignity, it does document increasing social inequalities, and it does faithfully record the pungency and power of everyday speech. It’s an urban sociology, an empathetic ethnography, a collection of valuable oral histories, and a morphology of ordinary people’s language all rolled into one.

But the book is a lot more than the sum of its parts. It tells us much that we already know and edifies us about much that we don’t, and it does more. It plucks startling beauty and poetry out of the cacophony of everyday life. It arranges it for us to contemplate and appreciate, not as a way to elide the injustices and indignities that permeate life, but as a necessary yet all too rare counterpoint. Khaled al-Khamisy reawakens our dulled sense of wonder, outrage, and sorrow, and that is an awesome achievement.

Like his first novel, Alaa al-Aswany’s 450-page second oeuvre is consciously designed to be a page-turner, and therefore it’s extremely readable, briskly-paced, and includes lots of details on sex, friendship, hatred, ambition, defeat, and other well-worn aspects of the human condition. Like ‘Imarat Yacoubian, Chicago is full of plausible, well-drawn characters whose lives intersect in a unifying locale, this time the University of Illinois in the American city of Chicago. The second novel also features the same narrative devices Aswany used in Yacoubian: a blunt denouement and bittersweet ending, an omniscient, sympathetic narrator, and more than a few bits of melodrama packed in at the end. As in Yacoubian, in Chicago Aswany carefully eschews any hint of formal experimentation, linguistic artistry, symbolism and metaphor, or any other literary devices. And perhaps that’s just as well if his laudable aim is to lure the layman to fiction reading and rebuild a novel-reading public (Chicago was first serialized in al-Destour). But Chicago lacks the blunt, resonant social critique that gives Yacoubian its edge and makes it such a phenomenon. In everything else, however, both novels tread the same ground in the same style.

Like his first novel, Alaa al-Aswany’s 450-page second oeuvre is consciously designed to be a page-turner, and therefore it’s extremely readable, briskly-paced, and includes lots of details on sex, friendship, hatred, ambition, defeat, and other well-worn aspects of the human condition. Like ‘Imarat Yacoubian, Chicago is full of plausible, well-drawn characters whose lives intersect in a unifying locale, this time the University of Illinois in the American city of Chicago. The second novel also features the same narrative devices Aswany used in Yacoubian: a blunt denouement and bittersweet ending, an omniscient, sympathetic narrator, and more than a few bits of melodrama packed in at the end. As in Yacoubian, in Chicago Aswany carefully eschews any hint of formal experimentation, linguistic artistry, symbolism and metaphor, or any other literary devices. And perhaps that’s just as well if his laudable aim is to lure the layman to fiction reading and rebuild a novel-reading public (Chicago was first serialized in al-Destour). But Chicago lacks the blunt, resonant social critique that gives Yacoubian its edge and makes it such a phenomenon. In everything else, however, both novels tread the same ground in the same style. In Chicago, Aswany trains a more analytical eye on his subject matter. The novel begins with a compelling, all-too-brief history of the city, from the massacre of Native Americans by European settlers in the 17th century to the devastating 1871 fire. Appropriately, the novel’s first words are an explanation of the city’s name: “Chicago” is the Algonquin word for “strong smell” that the city’s natives gave to the onion fields that covered its terrain. To signal the motif of human reinvention and survival running throughout the novel, Aswany’s introductory urban history highlights the resilience and recovery of the “Windy City’s” inhabitants after the Great fire, a conflagration that claimed 300 lives, rendered 100,000 people homeless, and destroyed $200 million worth of property. Admiringly, almost proudly, Aswany relishes the speedy, determined recovery of “Chicagoland,” “Second City,” “City of the Big Shoulders,” “City of the Century.” He then delves into his engrossing narrative of Egyptians, Egyptian-Americans, and Americans fumbling for meaning in the giant metropolis, a city the novelist knows well from his days of graduate study there in the late 1980s.

It’s not a coincidence that the novelist begins (and ends) with Shaimaa Muhammady, the very Egyptian name he gives to the very Egyptian, 33-year-old medical student from Tanta studying for her doctorate in histology at the University of Illinois. Shaimaa gets the lion’s share of the narrator’s affection, and perhaps for this reason is one of the most well-crafted characters (though not without some annoying made-for-TV clichés here and there). Like Buthaina al-Sayed of ‘Imarat Yacoubian, Shaimaa is an archetype of the driven, resilient Egyptian woman, a kindly creature struggling to survive in an inhospitable world. Shaimaa, however, is subjected to subtler pressures than Buthaina. The extremely hardworking, plain, muhaggaba medical student goes straight from Tanta to Chicago, mostly to escape social pressures at home in the form of relatives and colleagues who frown upon her academic excellence and unmarried status (Aswany draws a link between the two).

But moving to Chicago is no relief, as Shaimaa experiences harassment and isolation in post-September 11th America. She copes with her crippling homesickness by intensifying her studiousness and reproducing comforting Egyptian rituals at home. An unfortunate but hilarious kitchen accident leads her to meet fellow Egyptian histology student Tareq Hasib, a wiry, surly, equally hardworking graduate student who’s devised his own rituals to cope with loneliness and his awkwardness with women. Their tense first encounter blossoms into romance and intimacy, a potentially maudlin subplot that Aswany uses to effect convincing transformations in both characters. To his credit, the author also uses the unlikely relationship to raise important questions about Egyptian marriage customs, particularly the dynamics of class and status.

As with Yacoubian, Chicago has a large cast of central and peripheral characters crafted with varying levels of depth and psychological insight. Ra’fat Thabet is a handsome Egyptian émigré professor of Histology and baseball enthusiast who has acquired all the trappings of the American dream: American wife Michelle, brand-new Cadillac, large house in a fancy suburb with dog. Thabet deeply disdains all things Egyptian yet can’t shake off some residual cultural traits. His internal contradictions burst to the surface when his only daughter Sarah runs off with a self-styled artist named Jeff and becomes a crack addict. By contrast, Thabet’s departmental colleague Muhammad Salah is gripped by a powerful nostalgia for his native country after a seamless 30-year sojourn in the U.S. He abandons his American wife Chris and retreats into his memories, gingerly establishing contact with his firebrand college sweetheart Zeinab Radwan.

Thabet and Salah’s colleague John Graham is an ageing, wise Hemingway look-alike and former radical from the 1960s who lives with a much younger African-American woman named Carol and her five-year-old son Mark. Dennis Baker is the department’s most senior and distinguished professor, a towering scholar of few words who supervises a third Egyptian graduate student: Ahmed Denana, the head of the Egyptian Student Association in the U.S. A fourth Egyptian student, leftist Nagi Abdel Samad, has a passionate but short-lived relationship with Jewish-American Wendy Schor. The affair ends partly as a result of the interference of Safwat Shaker, the intelligence attaché in the Egyptian embassy who works closely with Denana to monitor Egyptian students studying in the U.S. During his American sojourn, Abdel Samad meets and immediately dislikes John Graham’s friend Karam Doss, a brilliant Coptic heart surgeon who emigrated to Chicago in the 1970s to escape discrimination in Egypt. But Doss rises above the experience in almost angelic fashion; he pipes in Umm Kulthum’s voice in the operating room, and when his bigoted former adviser seeks his help 30 years later, he graciously complies. By the end of the novel, Doss and Abdel Samad’s initial mutual dislike evolves into a close, conspiratorial but not altogether convincing friendship.

As much as he indulges and empathises with nearly all of his characters, Aswany heaps bilious contempt on Denana and Shaker, two agents of the corrupt Mubarak regime. The author seems to relish depicting them as a fraud and predator, respectively. Denana is a failed student who owes his academic standing to his lifelong collaboration with State Security officials; he’s a cheapskate, a liar, and treats his wife Marwa horribly to boot. And Shaker is a womanizing sadist who preys on the poor, broken wives of the Islamist activists that he persecutes and imprisons. To drive home the point, Aswany is keen to portray both men’s base natures by ascribing to them revolting sexual habits.

Aside from a handful of obvious political commentaries, Chicago has few social messages. It eschews preaching and didacticism in favour of a compelling portrayal of contemporary American life, with all its triumphs and failures. The land of opportunity that rescued Doss from discrimination excludes its own citizens, as the subplot involving Carol makes clear. The values of the land of freedom that Thabet praises also frown upon his instinctive protectiveness towards his daughter. And the land of licentiousness routinely condemned by Egyptian conservatives is the setting for a touching romance between Tareq and Shaimaa that would scarcely have been possible in Egypt. Aswany’s narrative also invites subtle connections between characters ostensibly belonging to different worlds and cultures. For example, Denana’s Egyptian wife Marwa and Salah’s American wife Chris have more in common with each other than with their presumptive peers. And as if to pre-emptively counter the reflexive, unthinking charge that Chicago is “anti-American”, two of Aswany’s most honourable, likeable characters are the Americans John Graham and Dennis Baker.

It’s clear that Aswany has ambitions other than the writing of serious literary fiction that nobody reads. His neorealist style avoids The Big Ideas in favour of the small dramas that animate everyday life. His narrative energy spurns highbrow symbolism and complicated structural devices in favour of straightforward, old-fashioned storytelling. In fact, both of Aswany’s novels read very much like screenplays. But so what? If this increases novel readership among the public and returns the novel to the centre of cultural life, bringing on film adaptations, public controversies, and imitation by younger writers, then Aswany will not only have breathed new life into a flagging neorealist genre. He will have created a new genre straddling the stuffy bastions of highbrow art with the cacophony of lowbrow entertainment.

But to avoid slipping into mass-market mediocrity, Aswany will have to start crafting more complex characters. He ought to resist the urge to continue to invent one-dimensional soap opera personages with no compelling inner lives, and instead plumb the rich tradition of afflicted, conflicted characters in the best works of Taha Husayn, Naguib Mahfouz, Tawfiq al-Hakim, and Yussef Idris.