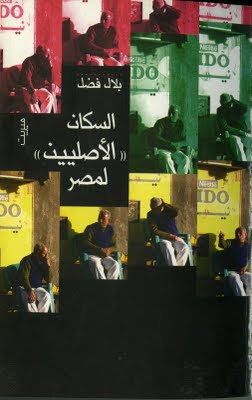

Bilal Fadl’s latest book has an attractive title and a laudable ambition. The irresistibly named The Original Inhabitants of Egypt: Stories about the Genius of the Place, the Idiocy of the Rulers, and the Indifference of the People (2009) promises to “narrate what I have seen and experienced of those human beings whom no one cares about, who harbour all the contradictions in the world and live in hope for a better fate in the afterlife.” Fadl has the credibility to pull this off. He was born into the category of Original Inhabitant of Egypt in 1974, his clever term for Egyptians who are neither rich nor middle class, but somewhere in the vast space beneath, what we alternately call lower-middle class, lower class, underclass, the marginalized, or the horrid “simple folk” (البسطاء). But despite his impeccable street cred, quick wit, and genuine affection for those he’s writing about, Fadl’s book falls flat. Unintentionally, it ends up being a condescending, forgettable series of ruminations about the woes of the little people.

Bilal Fadl’s latest book has an attractive title and a laudable ambition. The irresistibly named The Original Inhabitants of Egypt: Stories about the Genius of the Place, the Idiocy of the Rulers, and the Indifference of the People (2009) promises to “narrate what I have seen and experienced of those human beings whom no one cares about, who harbour all the contradictions in the world and live in hope for a better fate in the afterlife.” Fadl has the credibility to pull this off. He was born into the category of Original Inhabitant of Egypt in 1974, his clever term for Egyptians who are neither rich nor middle class, but somewhere in the vast space beneath, what we alternately call lower-middle class, lower class, underclass, the marginalized, or the horrid “simple folk” (البسطاء). But despite his impeccable street cred, quick wit, and genuine affection for those he’s writing about, Fadl’s book falls flat. Unintentionally, it ends up being a condescending, forgettable series of ruminations about the woes of the little people. Fadl is refreshingly honest about his “crossing over” to become part of the minority elite category, what he acidly calls The Inhabitants who Benefit from Egypt. He’s also frank about the irony that his embourgeoisement derives directly from his success at depicting the little people on screen. Fadl is now one of the most prominent screenwriters in Egypt, a trendsetter in the genre of ‘youth films’ and ‘shaabi films’, or rather, films featuring over-the-top, stereotypical lower class characters (with the outstanding exception of Wahed min al-Naas, 2006). Before that, he was a leading member of the feisty al-Destour team in its first incarnation (1995-1998), and he continues to be an editor at al-Destour. Indeed, Fadl made his name as an up and coming young practitioner of the Ibrahim Eissa school of journalism, a style characterized by pungent, ‘ammiya-laced prose; unambiguous and uninhibited criticism of rulers and their abuses; and plenty of hilarity to enliven the writing.

Not surprisingly given his current métier, the 29 essays in The Original Inhabitants of Egypt feature several stereotypical lower-class characters who the author presumably interacts with and then reports back to us readers. Inevitably, these caricatures speak in down-home, salty street argot, have wacky names and oh-so-eccentric habits, revel in conspiracy theories, and hold firm to the view that both the government and the opposition are welad kalb. Notwithstanding this unassailable last opinion, Fadl’s Original Inhabitants end up being extremely contrived, two-dimensional archetypes who we’re made to laugh at, not empathise with. They’re appendages of his middle class life, not real human beings with interests, foibles, and aspirations. Fadl regales us to “conversations” with the newspaper seller; his housekeeper Um Hind, who likes to call herself a “housekeeping manager” and yells at the TV screen when Hosni Mubarak is giving a speech (we’re supposed to chuckle on cue here); the fuul cart vendor, the makwagi, the bawaab, his friend’s chauffeur, unemployed patrons of a shaabi ahwa, and on and on down a list of stock figures from the underclass.

Instead of conveying Original Inhabitants’ work conditions or their emotional lives or simply straightforwardly narrating their experience of living a dispossessed life, Fadl parades before us a cast of made-for-TV stereotypes that we’re supposed to feel pity for. I understand that he wants to neither romanticise nor demonise Egypt’s denizens, a laudable aspiration, but surely there’s a better alternative than the mediocre stuff he’s penned here.

And an alternative there is, right in the same book. In a handful of essays, Fadl absolutely shines as a narrator and observer. These are passages where he recalls painful and hilarious experiences that he’s been through, back when he was an Original Inhabitant. One brilliant essay called “Why I hate Rahman Tables,” recalls a harrowing experience during Ramadan when Fadl was a lonely college student far from home. Against his instincts, he decides to break fast in the company of others at a local mosque; his description is one of the most outstanding tragicomic pieces I’ve ever read. It’ll make you laugh out loud while breaking down in tears. Another in the same vein recalls the first day of Eid when Fadl was a child, featuring the same touching mixture of hilarity, pathos, and startling insight.

The book’s last essay is a riveting piece titled “An Account of an Incomplete Popular Revolt in Heliopolis,” describing an incident that Fadl witnessed after Friday prayers one day in the posh Cairo neighborhood. The event itself is insignificant and routine: mosque-goers have a standoff with police who are attempting to confiscate some street peddlers’ merchandise. But Fadl’s beautiful description turns it into an eloquent, evocative allegory, one that ironically gives the lie to the book’s title.

These three pieces alone are nearly enough to erase the sour taste left by the rest of the book’s contents. Would that Fadl had dispensed with the reductive instincts of the pandering screenwriter, and gave free rein to his considerable skills as a participant observer and independent journalist. He could’ve written a perfect book.